Creating music is becoming increasingly easier and more creative as technology advances. There are some amazing (most for free!) tools online that really sparked my creativity. This article lists some of my favourites, along with links, so that you too can try them out and get inspired!

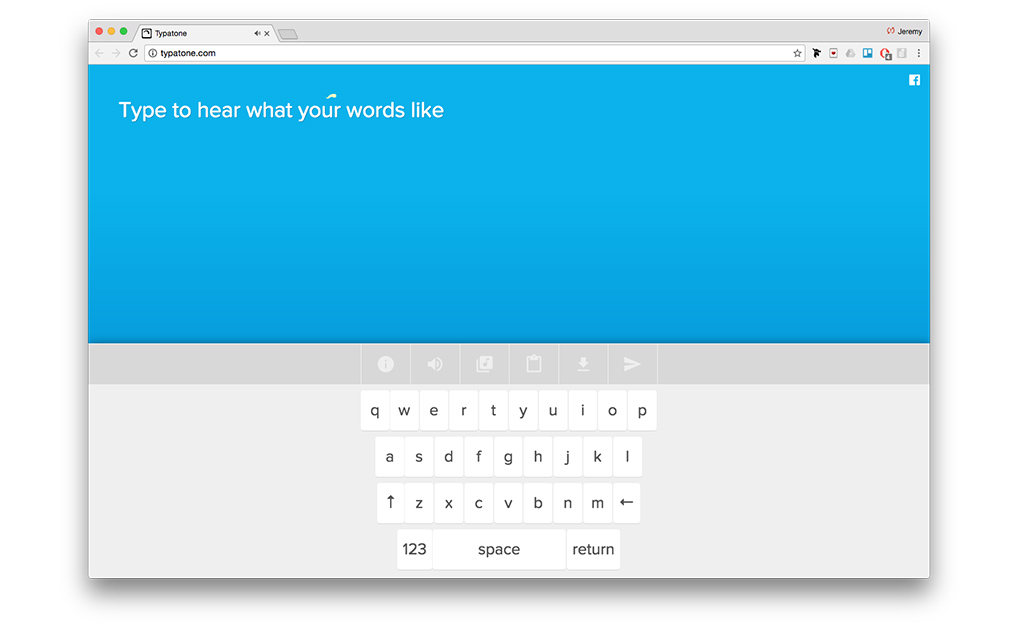

Typatone

Type anything into Typatone and it will turn every letter into a beautiful sound. Switch the instrument to find what you like best. There’s tons of option. You can transform any text into ambient music by copy-pasting it into Typatone or just writing it straight inside the editor. Cool tip: check how your name sounds! There is a download button so you can save all your creations.

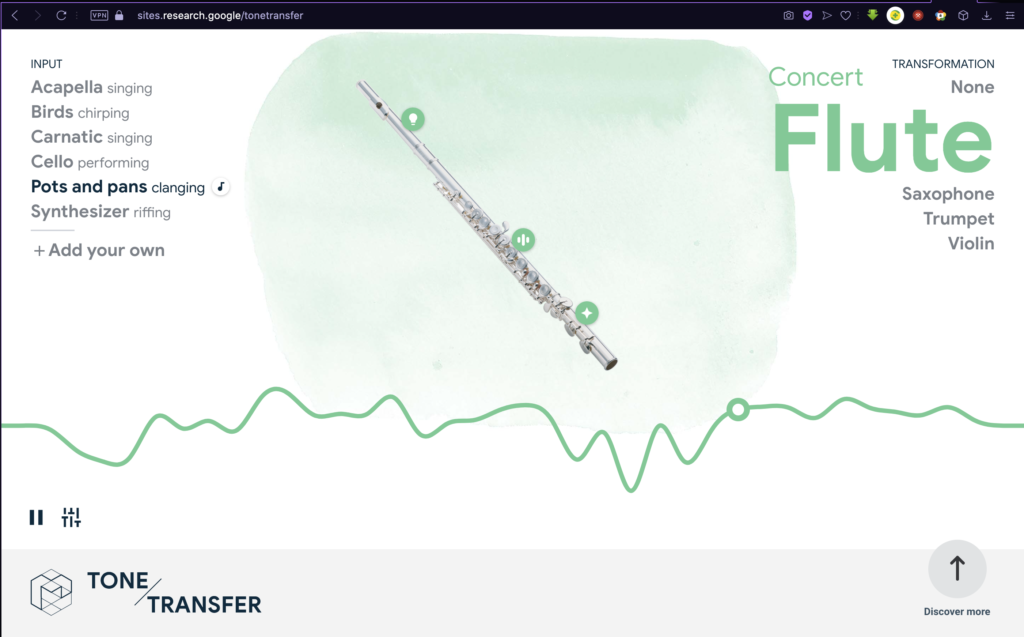

Google ToneTransfer

This tool is extremely appealing from a sound design perspective. It allows you to create completely nw instruments/textures out of your own recordings. The online tool has a few instruments available into which you can morph your recording. The transformation works on the principle of formant transfer. Google recommends trying how your voice sounds as a different instrument! Try using random objects or other instruments and then turning them into anything from the given list. Sometimes, the results are quite realistic, but sometimes the software produces weird textures/sounds, which can sound quite cool and unique. Try ToneTransfer here.

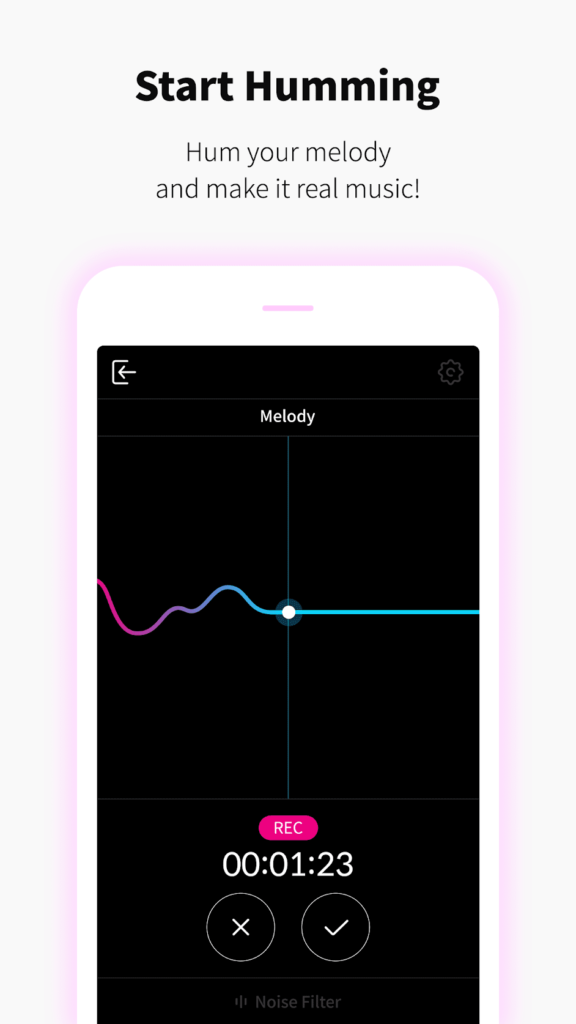

HumOn App

This is a very easy way to help make music. Simply, hum the memory into your phone microphone and the app will generate MIDI. HumOn is especially good if you want ideas on what to make. It has additional features, sounds and loops which enable you to create more than just a simple melody. This app is far from the best, but it is quite fun to use. The humming can go off key when the app records it, but it isn’t something to be too mad about. HumOn is both iOS and Android- compatible.

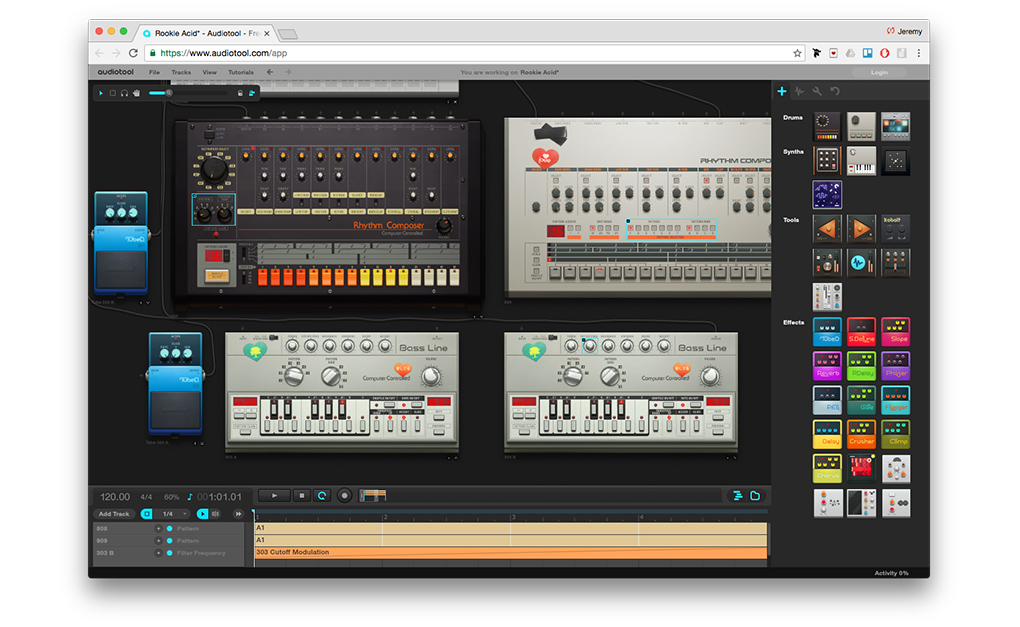

Audio Tool

AudioTool is an online production studio that feels like a real studio. You can play with iconic gear, like TR-909s, TR-808s and TB-303s just to name a few. Customise your setup as much as you want- all for free! Plug cables and tweak knobs manually. It’s all saved in the cloud. There’s also loads of tutorials to watch.

Interactive YouTube Instruments

There’s a whole culture of interactive videos on YouTube that I just discovered. And a lot of them are playable instruments! How does it work. The author uploads a video consisting of one shots of a chosen instruments. You can skip through timestamps by using the number pad on your keyboard. So basically, the number pad is now your MIDI keyboard. Frankly interactive YouTube videos are a very creative way of creating a cool user experience through videos. The channels Amosdoll Music and Play With Keyboard seem to be the most prominent in this field of music creation.