This article talks about some of the Sound Art projects/installations that serve as an essential guide to the art of sound design. The list contains diverse types of works featuring interesting perspective and a different approach to sound.

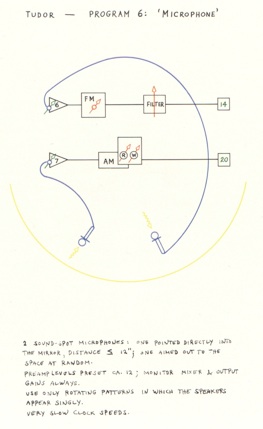

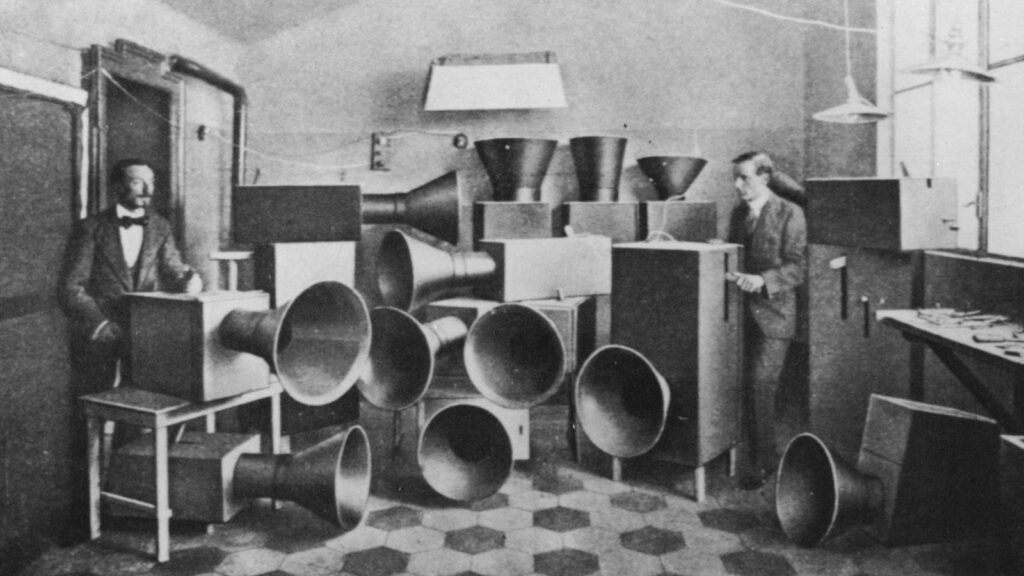

Luigi Russolo, Gran Concerto Futuristico (1917)

Luigi Russolo is perhaps best known as a painter associated with the Futurist movement in Italy. However, he is also considered one of the earliest (maybe even first) experimental noise painters. Inspired by World War I factory equipment and guns, he invented and built an acoustic noise generator called Intonarumori (meaning “noise source” in Italian). In 1913 he published the Art of Noises, in which he argued that the evolution of urban industrial soundscapes required a new approach to music. For Russolo, melodic music limited the human potential for appreciating more complex sounds. In 1917 he attempted to correct this in his play Gran Concerto Futuristico, for which he put together a noise orchestra playing offending sounds (Music did not sound classical.) Despite the widespread criticism he faced in connection with this piece, he continued to perform well after World War I. Today, his manifesto is considered one of the most important texts in 20th-century music theory.

Marcel Duchamp, Erratum Musical (1913)

Marcel Duchamp was fascinated by how he was able to visualise sound. He said: “You can’t hear the gossip.” Despite being untrained, he was composing music between 1912 and 1915. The end result was radically different from the off-the-shelf Dada model that made him famous. He developed one purely conceptual piece and two conceptual exercises to play, including the Erratum Musical, a randomly arranged sheet music composed for three voices. Duchamp created three sets of 25 cards. F (from F below middle C to F high) with 1 entry per card. Cards are shuffled in the hat and then drawn one at a time. Then I wrote a series of notes in the order in which I removed the cards from the hat. Performers can decide how they want to perform their piece. Duchamp did not give a score in this regard.

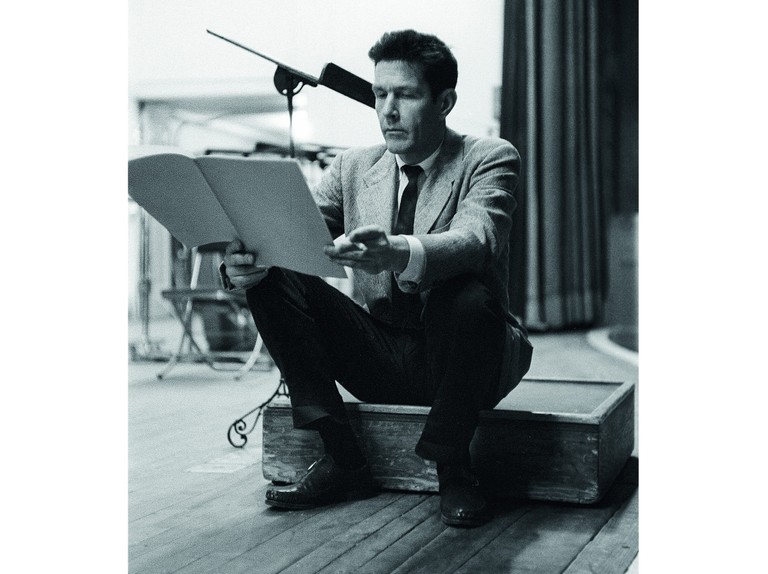

John Cage, 4’33” (1952)

For his masterpiece, Cage explored the potential of silence, revolutionising sound art and performance. He is best known for his composition of 4:33 seconds, a three-part composition of 4:33 seconds of silence. Inspired by a visit to the anechoic chamber at Harvard University, the work is not known to contain anything special. The performer is invited not to play the instrument or make any noise. However, no silence is truly silent, and the audience is keenly aware of the sounds of the environment during pauses. This koan-like paradox was based on what Cage heard in a Harvard auditorium. He discovered that he could hear his own heartbeat. He wrote of the experience, “I will hear it until I die.” “And they will continue after I die. You don’t have to be afraid of the future of music.”

Bill Fontana, Distant Trains (1984)

By the 1960s and early 1970s, advances in digital media increased the opportunities of visible artists and composers running on the intersection of sound and sculpture. Bill Fontana become a pioneer in growing sculpted sound maps for city environments. At the “Remote Trains” exhibition in Berlin for a month in 1984, a loudspeaker become buried withinside the web website online of the previous Anhalter Bahnhof Station, one in every of Europe’s busiest teach stations earlier than World War II. It become destroyed with the aid of using bombing at some stage in the conflict and become formally decommissioned in 1952. A stay microphone become housed withinside the Köln Hauptbahnhof, which recreates the phantom sound surroundings with the aid of using transmitting acoustics in actual time from the noisy station to the deserted Anhalter Bahnhof.

Max Neuhaus, Times Square (1977–92)

Max Neuhaus’s most famous work is a pulsating drone that fires 24 hours a day, 7 days a week from a subway steam hatch at the northern tip of Manhattan’s triangular pedestrian island. (Thanks to the MTA and the Dia Art Foundation, this work is permanent near Times Square.) Inside it, the pitch and pitch change as passers-by move around the block. “A rich harmonic sound texture reminiscent of a large bell after a bell is ringing is impossible in this context,” Neuhaus said. “For those who discover and embrace the impossibility of sound, the island becomes another place that includes its surroundings but is separate.”

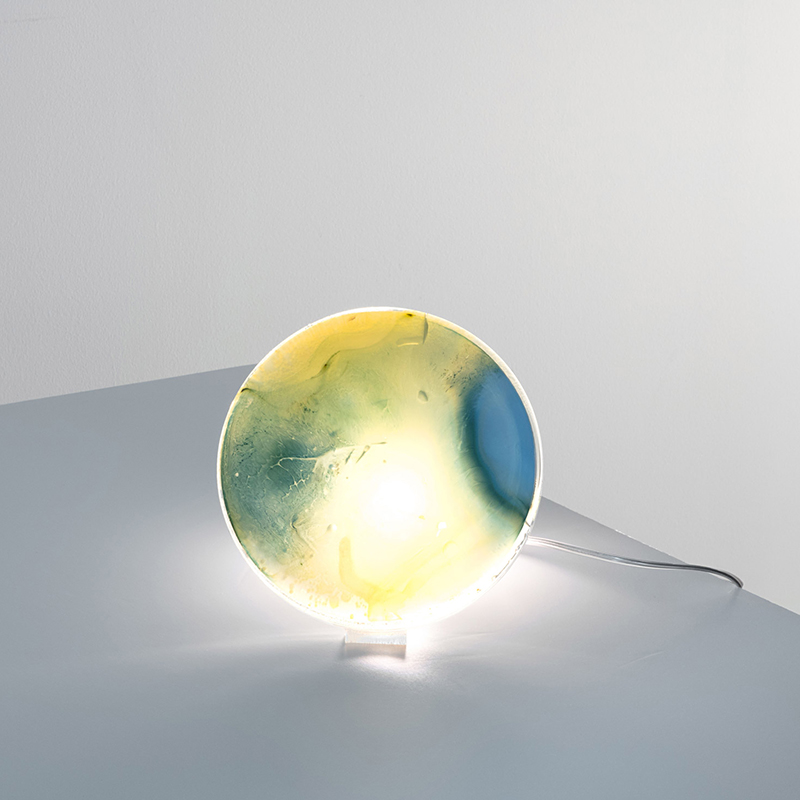

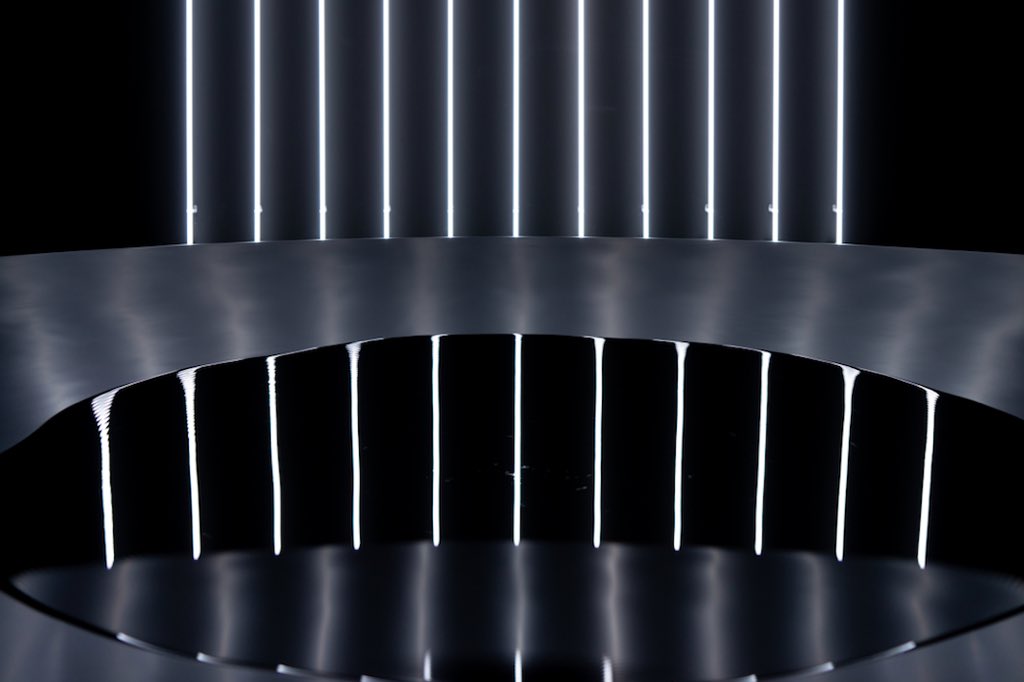

Carsten Nicolai, Reflektor Distortion (2016)

Berlin and Chemnitz artist Karsten Nikolai has been working since the 1980s at the intersection of sound media, science and the visual arts. Nikolai, co-founder of the influential “sound not sound” electronic music label RasterNoton, has exhibited sound and video installations twice: at Documenta X in Kassel, Germany and at the Venice Biennale, Italy. Much of his work is aimed at creating sound and light phenomena perceived by the human eye and ear. In 2016 he presented the Reflektor Distortion at Galerie Eigen + Art Berlin, where a rotating water bass strikes through a speaker at a low audible frequency. The ripples in the water reflected the frequency of the waves, making the sound visible only for a short period of time.

Jem Finer, Longplayer (1999)

On December 31, 1999, the British musician and artist Jem Finer began playing a piece of ambient music that will finish in the year 3000. Provided humanity endures another 1,000 years, Longplayer will be the most epic piece of music ever performed, outstripping John Cage’s 639-year-long organ concert currently taking place in a church in Halberstadt, Germany. Longplayer is housed in a lighthouse in London and processed by a computer algorithm that mechanically extends the sound of a single instrument consisting of 234 Tibetan singing bowls. The sound is without repetition or break. “The intention [of Longplayer] is that its droning and parping will, like this year’s eclipse, make the hearers ponder the passing of time in a way that makes you feel both mortal and insignificant,” wrote the Evening Standard on the night of its commencement in 1999.

Christian Marclay, Recycled Records (1980–86)

For nearly 40 years, Swiss-American sound artist and experimental DJ Christian Marclay has manipulated sound into physical form through photography, sculpture, installation, and performance. The artist is credited with pioneering an experimental form of turntablism, in which sound is altered through multiple turntables. Inspired by the noise experiments of composer John Cage and early hip-hop DJs, Marclay began incorporating prerecorded dissonant sounds produced by vinyl records in motion into his turntable performances. In the seminal series “Recycled Records,” the artists sliced apart vinyl records and reassembled the pieces to create new arrangements.

Susan Philipsz, Lowlands (2010)

The Scottish-born, Berlin-based artist Susan Philipsz uses site-specific sound installations to probe the link between sense and memory. “Sound is materially invisible but very visceral and emotive,” she once said. “It can define a space at the same time as it triggers a memory.” In 2010, she was awarded the Turner Prize for the sound installation Lowlands, the first work of its kind ever to earn an artist the famed award. In the winning iteration of the piece, Philipsz performed three variations of a Scottish lament about a drowned lover who returns to her lover’s dreams, beneath three bridges over the River Clyde during the Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art. The Turner judges also considered Long Gone, in which a recording of the artists singing the eponymous Syd Barrett song played at the entrance of the Museo de Arte Contemporánea de Vigo in Spain. Her win attracted criticisms from detractors who argued that she should be classified as a singer, not an artist. The judges, however, insisted otherwise.

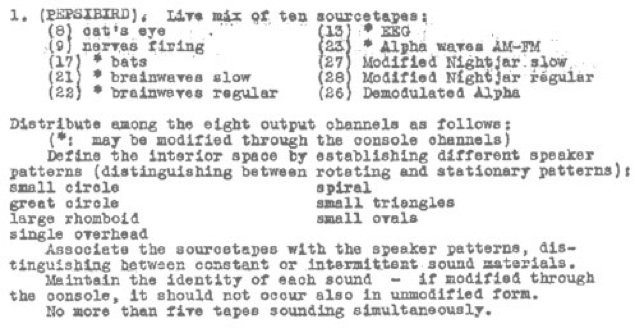

Samson Young, For Whom the Bell Tolls: A Journey Into the Sonic History of Conflict (2015)

A traditionally trained composer, Hong-Kong based Young has been on the rise since he won the inaugural edition of Art Basel’s BMW Art Journey Award in 2015 for his project For Whom the Bell Tolls: A Journey Into the Sonic History of Conflict. Over two-months, he documented the chime of iconic bells across five continents. He then crafted responses which explored the bells’ status as musical instruments and political, social, and religious representations of their communities. In June 2016, he drew critical acclaim at Art Basel Unlimited for a similar exploration into the militarization of sound. Seated atop a booth-sized cube and dressed in police uniform, Young performed with a Long Range Acoustic Device, a sonic weapon used to disperse crowds at protests. A low level form of the weapon is also used to repel birds from private properties, which Young represented by recreating distressed bird calls.

Christine Sun Kim, Close Readings (2015)

Berlin-based artist Christine Sun Kim centers the systemic barriers attached to deafness. Kim was selected for the 2013 MoMA exhibition “Soundings,” the museum’s first major show dedicated to sound art. In 2019, a group of charcoal drawings by Kim were included in the Whitney Biennial. The work, along with the piece One Week of Lullabies for Roux (2018), became the first sound art installations acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2020.

Resources

www.artnews.com/feature/sound-art-guide-most-famous-works-1234572580