Procedural Narratives ist eine Designtechnik, in der die Erzählung einer Geschichte aus vielen Bereichen besteht, welche in beliebiger Reihenfolge erkundet, erlebt und interpretiert werden kann. Eine sehr gute Anwendbarkeit dieses Prinzips findet sich vor allem in der Videospielbranche wieder, da die permanente Interaktivität des Spielers ein Grundbaustein für ein immer einzigartiges Storytelling sein kann.

Die Definition von Procedural Storytelling darf und kann jedoch nicht mit anderen prozeduralen Vorgängen, beispielsweise dem Procedural Modelling, verglichen werden. Diese sowie viele weitere Gebiete der automatisch generierten Erstellung von Content spezialisiert sich ausschließlich auf die visuelle Umsetzung digitaler Produkte. Ziel dieser Vorgänge ist es, manuelle Handarbeit zu minimieren und durch Algorythmen zeitintensive Vorgänge in möglichst kurzer Zeit in die Tat umzusetzen, während die Qualität nicht darunter leidet. Das Procedural Storytelling beschäftigt sich keinerlei mit visuellem Content, sondern ergibt sich hierbei aus dem Produkt des spielerischen Inputs und die vom Designer vorgegebenen Ressourcen. Welche Kommunikationsart das Spiel verwendet um ihre Geschichte zu erzählen, ist absolut gleichgültig und tut hier nichts zur Sache, denn die entscheidende Rolle in Procedural Storytelling ist das Verhalten des Spielers selbst – nicht die Erzähltechnik. Er entwickelt durch seine Entscheidungen den Verlauf der Geschichte und passt ihn ganz personalisiert nach seinen eigenen Vorstellungen an, sofern das Leveldesign diese Art von Gameplay zulässt. Je weiter dieses Konzept in ein Spiel implementiert wurde, desto “freier” fühlt sich der Spieler, wenn es um persönliche Entscheidungen und die Verantwortung für den weiteren Verlauf der Geschichte innerhalb des Spiels geht.

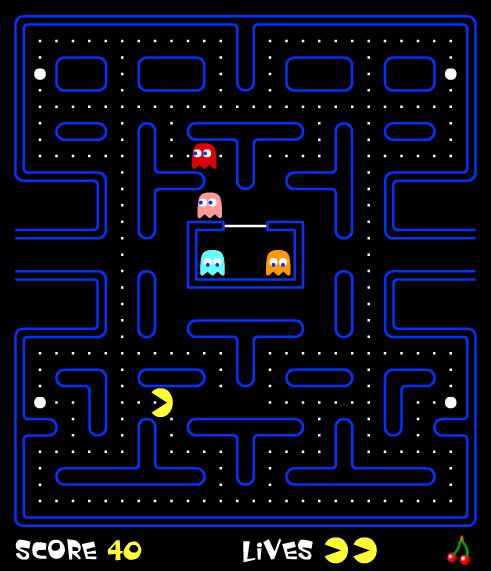

Frühere Videospiele verwendeten dieses Prinzip um ein einzigartiges Gameplay im Spiel zu erstellen. Auf diese Art und Weise ist es beispielsweise den Entwicklern von Pac-Man gelungen, jede einzelne Runde abwechslungsreich zu gestalten, da jede Runde unterschiedlich gespielt wird und dem Spieler vor neuen Herausforderungen stellt. Das Prinzip von Procedural Narratives und deren Funktionsweise in Videospielen lässt sich mithilfe des einfachen Spielprinzips von Pac-Man sehr einfach erklären.

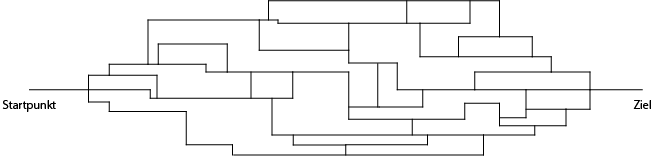

Pac-Man bzw. der Spieler hat ein Ziel – jedoch hat er unzählige Möglichkeiten, dieses zu erreichen, da viele tausende Wege existieren, die alle zum gewünschten Ziel führen.

Während dem Spieler eine „volle Kontrolle“ der derzeitigen Situation jedoch nur vorgespielt wird, ist der Start- und Zielpunkt vordefiniert und bleibt bis zum Ende hin unverändert. Welche Aktionen der Spieler jedoch zwischen diesen beiden Komponenten tätigt, steht ihm frei zur Auswahl. Weiters ist das Navigieren innerhalb des Labyrinths aufgrund einer eingegrenzten Fläche beschränkt. Natürlich ist der Person diese Tatsache bewusst, doch wird dies mit diversen Aufgaben, die der Spieler zu absolvieren hat, meist in den Hintergrund gerückt.

Profit: Nicht nur das Spiel ist ein einzigartiges Stück Software – es unterscheidet sich ebenfalls jeder einzelne Durchgang und fördert somit die Langlebigkeit eines Spiels enorm.

(Following content is WORK IN PROGRESS)

Overview of Three Techniques for Procedural Storytelling:

Simulation:

Bei diesem Ansatz lassen wir Charaktere nach bestimmten internen Regeln entwickeln, und Sie lassen zu, dass die Geschichte im Laufe der Zeit autonom entsteht. Sie platzieren eine Reihe von Zeichen in einem geschlossenen Raum und sehen, wie sie reagieren.

You can just run the simulation and see the story unravel under your eyes. In fact, another drawback is that you have no control over the story. Moreover, most of the stories are not enjoyable (as in life: not everyone’s life is worth a book or a movie). Therefore, the player needs to search for and reconstruct interesting stories actively. Like an archeologist. On the other hand, some people love this extra work.

Storytelling via Planning: (…)

Procedural Storytelling via Context Free Grammar: (…)

Quellen:

cubicleninjas (2021): Procedural Storytelling And Its Future In Marketing. In: https://cubicleninjas.com/procedural-storytelling-and-its-future-in-marketing/ (zuletzt aufgerufen am 10.05.2021)

Aversa, Davide (16.03.2020): Overview of Three Techniques for Procedural Storytelling. In: https://www.davideaversa.it/blog/overview-procedural-storytelling/ (zuletzt aufgerufen am 10.05.2021)

Mcrae, Edwin (2021): Procedural Narrative: The Future of Video Games. In: https://www.edmcrae.com/article/procedural-narrative (zuletzt aufgerufen am 10.05.2021)