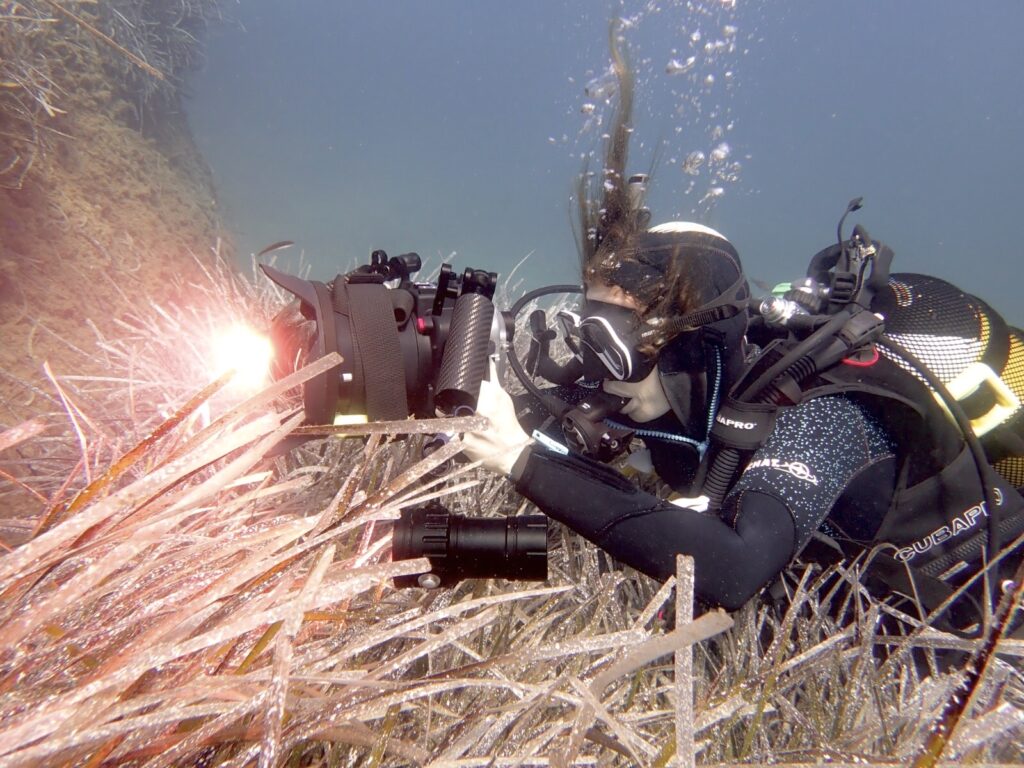

When getting more serious into underwater filming there are a couple things to think of. First of all you will probably want to upgrade from an action camera to a camera housing for the camera you use on land. To have the right gear when being underwater is important, and with gear I do not only mean camera gear, but also your diving gear. The most important thing when filming underwater is that you as a diver are safe and are already a good diver before concentrating on anything else under the water surface.

Author: Sabine Probst

What is a script?

Documentary scripts tend to evolve over the course of production. In the case of programs that are significantly driven by narration, the script might begin to take shape during pre-production, only to be significantly revised and rewritten during editing. On programs in which narration augments visual storytelling, scripts are not usually written until editing or shooting is complete (or nearly complete). At that point, filmmakers will assemble a paper script. This script builds on the original treatment but takes into account changes to the story as filmed, and it incorporates interview, sync, and archival material in proposed screen order as a blueprint for the editor to follow. As editing progresses, this script is revised and rewritten, until no more changes are made. Not all films are edited this way. (Curran Bernard 2004, p.122)

What is a Treatment?

A treatment should be short, about two pages for a feature documentary. This is not a script. A treatment is a summary of how the subject will be approached, and it should generally elaborate on the concept. The treatment gives a feeling of where the story will go, beginning, middle and end. Important in the treatment are the issues that will be explored and what questions will be asked. The treatment should give the reader a sense of who, what, when, why, where and how. Written well it can help build interest in the documentary. (Martin 2018, p. 133)

A treatment that gives a strong notion of the envisioned documentary could be presented in a number of mediums including film or video trailer, photographic, portfolio, audio program or slide presentation. A well thought out concept and treatment provides a place to begin and it brings the idea to life.

What is an outline?

Quotes from research:

Outlines:

An outline is a sketch of your film, written to expose its proposed and necessary elements. In most cases, the outline is a working document for you and your team.

It would include a synopsis (one or two paragraphs) of the overall film story, and then a program outline broken down by acts (if applicable) and then a program outline broken down by acts (if applicable) and sequences, with detailed information on elements such as archival footage or specialized photography and interviews. (Curran Bernard 2004, p.115) The outline is a chance to begin imagining your film. (Curran Bernard 2004, p.116)

Be careful to focus it as you intend (for now) to focus the final film. (Curran Bernard 2004, p.116) || What is the film about? Who’s story are you telling

If the film is about events in the past or events you have control over (a series of demonstrations set up for the purpose of an essay for example), it’s easier to begin outlining the film and finding an appropriate structure. For films of events that will unfold as you shoot, it’s possible to draft an outline (and treatment) based on what you anticipate happening. (Curran Bernard 2004, p.116)

What is the environment?

What we call “the environment” is both a complex natural ecosystem, and a socially constructed abstraction.

The cognitive split between humanity and nature—indeed, between the spiritual world and the material—derives from the very earliest religious texts. (Duvall 2017, p.15)

The human species seems to be unique in its ability to cognitively disassociate itself from the natural world. Writes Willoquet-Maricondi (“Shifting Paradigms,” 2010): “We have erected a social structure, a civilization based on a perceptual error regarding the place of humans in the biotic community”. (54-55) (Duvall 2017, p.16)

History has been significantly marked by the ability of humankind to control natural processes and resources to serve its energy needs—in the beginning with fire, wood, water, wind, and metals, later with fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. The rise of mercantilism and imperial conquest established the supremacy of societies that could excel at invention in the fields of exploration and weaponry. (Duvall 2017, p.16)

Perhaps the first systematic challenge to the vision of technological progress emerged in 1864 with George Perkins Marsh’s Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. Marsh wrote one of the earliest explications of the ecological principle, noting the destructive effects of human activity on the natural world throughout history. (Duvall 2017, p.17)

From the visionary moral leadership of Sierra Club founder John Muir and the political support of avid outdoorsman President Theodore Roosevelt, the US Congress passed a series of laws creating a system of national parks. This “first wave” of environmental activism focused on conservation and preservation, recognizing that Americas’s natural resources were not as inexhaustible as previously believed. (Shabecoff,1993)

During the post—World War II period of conservative politics and economic expansions in the United States, environmentalism again took a back seat in the public mind. But beneath the surface, important thinking was going on. Aldo Leopold, author of Sand Country Almanac (1949), developed his concept of a “land ethic,” a scientifically based re-visioning of the relationship between humanity and nature that alerted man’s role from conqueror of the land to citizen upon it—just one living species among others in an interconnected web of life. Biologist Rachel Carson, whose 1951 book The Sea around Us was adapted into a feature length documentary film, also wrote Silent Spring in 1962, documenting the threats posed to humans and other species by pesticides, and bringing ecological issues to the attention of a broad public as well as the government. These thinkers and many others challenged the dominant paradigm of infinite growth and human hubris, increasingly regarding society in terms of systems thinking instead of ideological economic or political orthodoxy. …the decade of the 1970s, two important events helped to focus the public imagination on the environment and encourage holistic environmental thinking. (Duvall 2017, p.18)

The first was the moon landing in 1969, accompanied by photos of Planet Earth from space—Carl Sagan’s “pale blue dot.” (Duvall 2017, p.18-19)

Seeing Earth as a unified whole, dominated by blue oceans with land undivided by national borders, led the Earth’s residents look at their planetary life in a more integral way. One manifestation of this new vision was the first Earth Day in 1970, which for perhaps the first time brought together all the related issues of conservation, consumerism, energy usage, pollution, and species extinction into an interwoven context. (Duvall 2017, p.19)

these are some quotes from my research

THE EDUCATION MARKET FOR DOCUMENTARY FILM: DIGITAL SHIFTS IN AN AGE OF CONTENT ABUNDANCE – master thesis evaluation

level of design:

I would say the person who wrote this thesis did not really pay attention on the design. The thesis is rather long, one font, two colors and multiple sizes, the smallest size is a little hard to read. It does not look like a designer made it, which is also not the case here. All in all design-wise it is ok to read, the font is not the best to rea in my oppinion and sometimes too small but it is readable.

degree of innovation:

The thesis is about the benefits of documentary practice in the Australian education sector as well as a valuable ancillary market for documentary producers and distributors. I know that some schools do show documentary films in schools, but I have never read about more deatils about how beneficial it really is, and there are also quite some books about film distribution. So I would say there is definitely some degree of innovation in the thesis, yet the topic is not totally new.

independence:

The thesis was written without cooperation with any other entities.

Outline and structure:

The outline describes in short the content of the thesis, which I think is done well. It brought to the point what the thesis is about. The structure is also very well done and everything is easy to find because of the well and very detailed structure of the table of contents. I am not too sure if I would made the table of content that long ( I would also have narrowed down the topic a little bit) but it definitely gives a very detailed few on what you can read in it.

Degree of communication:

The communication is good in my opinion, it is well to see what a quote is, though maybe a glossary would have been nice, in case someone who is not a filmmaker or film studies expert and wants to read this. But you can see throughout the whole thesis, it is not written for someone who has no knowledge about film yet.

Scope of the work:

The scope of the work is to show that the education sector in Australia has proven both a beneficiary of documentary practice as well as a valuable ancillary market for documentary producers and distributors. Digital distribution and access have contributed to unparalleled levels of choice for educators around the documentary content they can deploy in their teaching. However, scarce scholarly work exists on how educators are navigating this new abundance of digital content and to what extent this new variety and volume of documentary may be assisting the sustainability of the documentary sector within the attention economy. Consideration of documentary’s function within concepts of cineliteracy in media analysis will frame this research alongside the potential of cineliteracy to enhance outcomes for all stakeholders within the education market for documentary. Central outcomes of the research will include strategic industry analysis; impacts posed by digital innovations in distribution; and the challenges and opportunities facing both the documentary industry and wider education sector. Analysis of the formal and informal outreach work of key international film festivals, foundations and charities connecting documentary with education audiences will be undertaken. Findings from this analysis include best practice observations which may allow for improved approaches to documentary distribution, delivery and implementation in the Australian education sector.-Ruari Baroona Elkington. I think the topic is really interesting, because I want to create eductaional documentaries in the future.

Orthography and accuracy:

I think the thesis was well thought through, researched and checked. I am not an expert in the field, but I saw a lot of quotations from different sources, which shows me that the author researched the topic well. I also dont see any mistakes which would stand out to my eye.

Literature:

The bibliography is about ten pages long, it consists out of books, magazines and web articles.

Film Festivals

“Film Festivals have been around a long time. The first event was the Venice Film Festival in 1932, with other major fests launching within the years after WWII, including: Locarno (1946), Edinburgh (1947), Cannes (1947), Melbourne (1951), and Berlin (1951). “ (1) Film Festivals are not only a great opportunity to show a new movie to an audience, but it is also a notable way of making connections in the industry. Under the visitors are not only interested viewers but often also people representing companies and organisations related to the festival. At more well known festival like Sundance it is not unusual that upcoming filmmakers are discovered and have the opportunity to start their career as a filmmaker on a higher level. Besides that it is a great chance to get to know other filmmakers, take part in workshops and talk more about the message of your film in Q&A sessions after your film is screened.

One popular website to submit films through is film freeway, browsing through this site it gets clear that there are a lot of film festivals out there. Yet not every festival is for every film. When planning a film the director should have an audience in mind, so as the film is done at the end of the process, the right festival for this audience needs to be found.

Most festivals do have a fee for submissions, so choose festivals wisely in order to spend your budget for the right festivals and increase the chance of your film being shown at festivals. It is also a good idea to think of where you want your film to premiere. “When planning your festival strategy, it’s important to think about them as marketing opportunities, but also knowing where you have a chance to shine. For example, while it`s great if you get invited to a top-tier festival, it can be difficult without a publicist or rep to get any attention with so many films. Yes, it’s always nice to get the indentation to Sundance, but too many filmmakers count on this. In 2017, they had thousands of entries for approximately 120 slots. Not good odds. And a number of smaller tests can give little films great opportunities.” (2)

Here a list of some documentary film festivals: IDFA, HotDocs, Full Frame, Sheffield, Silver Docs, Thessaloniki, True/ False, DC Environmental, SXSW, Doc NYC

Top 25 Film Festivals:

Sundance

IDFA & Toronto

Hot Docs

Sheffield Doc/ Fest

Berlin

Silverdocs

Tribeca

SXSW

Los Angeles

CPH:DOX

True/False

Full Frame

Ambulante/ Morelia

Jihlava

San Francisco

Edinburgh

Thessaloniki

Camden

Sarasota

Doc Lisboa

DokuFest Kosovo

Denver

Traverse City

Ashland

There are also a lot of smaller festival which are especially for environmental films like the Jackson Wild Film Festival (the nature equivalent to the Oscars), Suncine, Environmental Film Festival Australia, International Environmental Film Festival Green Vision, Planet in Focus International Environmental Film Festival (Canadian Screen Award Qualified), Colorado Environmental Film Festival, CinemAmbiente-Environmental Film Fest, Wild and Science Film Festival, Envirofilm, Save the Waves Film Festival, International Ocean Film Festival, Blue Ocean Film Festival & Conservation Summit, and many more.

There are many things to think about when submitting a thing, the three most important ones are:

-the budget: When thinking of the film festival budget, it is important to not only focus on the costs for submissions. When the film gets selected the director and some members of the crew might want to make appearances at a couple of the festivals. Some festivals do pay for accommodation or transport, but in general, it’s better to plan a budget for appearances.

-the timing: The timing of the release should be planned after knowing to what festivals the film is going to be submitted. Festivals do have deadlines and most festivals are yearly, so if the deadline is missed the release has to be pushed back a year. A lot of filmmakers plan the release of their film based on the Sundance deadlines, if you choose to do so, have a back up plan or more than one. Most filmmakers submit their films to a lot of film festivals expecting to get accepted at a few, which is a realistic point of view, especially if the film does not show any revolutionary footage or has a world star in it.

-the goal: The goal of the film should be clear from the beginning, the right film festival can bring the filmmaker closer to reaching this goal. It could be to find distribution opportunities or just to show the film to the wanted audience.

underwater filmmaking part one

Underwater filming

As with filmmaking on land, the right gear is also very important on land, and the right setup of this gear is even more important. Underwater image systems have two main components, the camera and the underwater housing for this camera. If the filming shall take place deeper, lights should be included, otherwise it will be very disappointing to see that the footage looks washed out. The deeper a diver goes, the more they will see that colors will get less and less vibrant, because less light from the surface goes down into the depth. Mounting video lights on the underwater imagining system allows the filmmaker to bring those lost colors back.

Lights are also needed when shooting in the night, as those are the only light source underwater that time of day. Light Absorption: There are multiple reasons why it gets darker underwater, one is that particles block the sunlight which is penetrating the water, as I previously mentioned water itself also absorbs light, and light also gets reflected of the waters surface. All of that reduces the amount of light we have underwater. With the light absorption the colours dissapear, First red, then orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. The longer the distance light has to travel through water, the less light comes through and the more colours will be lost. This can make underwater images look very unappealing. Red loses its vibrance at around 4,5m, orange at 15m, yellow at a 30m, green at 76 followed by blue and violet. Most underwater camera housings come at a very high price, so it is best to research for some time before deciding on one housing. Those expensive housings for the most part also only fit one specific camera model, which means not only the choice for the housing manufacturer should be thought through but also which camera system will be used. For the beginning waterproof action cameras, soft plastic housings or even phones in waterproof cases can be used. Those options are much cheaper than a professional underwaterhousing for the film camera of your choice. But of course the price difference is visible. Cheap soft plastic housing are also not meant for deep dives.

Suspended Particles: Suspended particles in the water affect the sharpness of the image, and can also cause backscatter (little particles which appear on your image) Sometimes there is nothing a diver can do about those particles swimming around in the water, but they can also be caused by the diver, if she/he gets to close to the underwater environment and touches rocks, plants, the ground or walls, if that happens little particles can get loose and start swimming around. A very good bouncy is key to good footage. Not only because it can cause an unclear picture but also because the camera needs to be held still in order to create smooth footage. No matter in which clarity of waters footage is filmed, light is deflected by particles in the water trough which it comes. Because of this process, sharpness is reduced, the more light travels through the more sharpness gets lost. If the goal is not to film macro, better not use a long lens, use a wide lens and get as close to the object which shall be filmed as possible. This way the distance between the lens and the object is shorter and less light in-between.

Another way where particles are made visible is through the video lights on the camera, if they placed to close to the lens. The light coming from your system will reflect on the particles and cause the snowstorm effect called backscatter. The solution for this problem would be to mount the lights far enough away from the lens, and to aim the strobe in the direction of the subject, but only minimal light is between the lens and the subject.

One camera setting which should not be forgotten about is white balance. This setting is as important if not even more important underwater than on land, especially when filming without lights. When filming in raw, this is not a huge issue, but cameras that film in raw are very expensive and need a lot of memory card space. If the camera allows it set the white balance manually, it is easy to bring a white card underwater or use white sand or a slate as reference. Another way to get the right color underwater is by using red or pink filters. They can be screwed on in the front of the lens or housing. Red filters for blue water, pink filters for green water.

Creation of environmental documentaries as a one person crew

There is a lot of information out there about filmmaking and documentary filmmaking. But not so much about environmental/ conservation or wildlife filmmaking. When thinking about making such a documentary most people would probably think of big productions like the once from BBC or NatGeo. Yet it is possible to create a documentary as a small crew or even alone. Films can have a great impact on its viewers, therefore well made environmental documentaries are important. Especially ones from independent filmmakers with the correct knowledge about the topic they are making a film of and no big production company in their neck telling them to stage things cause of better quotes.

For my master thesis I want to write a little handbook like I wish would already exist. One which is easy to understand for everyone, where you can’t only read about how to make a documentary, but also get an overview of what an environmental documentary is, its history, its power and eco critical perspective and environmental ethics. After having an understanding of that I will go through every step of production, from research, finding protagonists to marketing, distribution and festivals. As environmental filmmaker I think it is also very important to have knowledge of the things you are making a film about, so there will also be chapters about what the environment is, conservation and conservation psychology. Obviously every project needs its own research about the specific topic the film is going to be about, but I think an understanding of the basics is important.

Alongside this book I am going to create a documentary film about the problems of Mediterranean Sea. This documentary is currently in its pre-production phase. First possible protagonists from different ocean conservation organizations were approached and first confirmations came in. As a second, smaller part of my master thesis book I am going to document the making of this film as a real life example, using the information I have gathered in the first part.

What is a documentary-film?

“The first use of the term in relation to film is generally attributed to British filmmaker John Grierson, who defined documentary as “the creative treatment of actuality” (Kerrigan and McIntyre,111). This definition attempts to reconcile the subject matter of a film — something that exists in the real world, as distinguished from fiction, wherein characters and settings are the product of a screenwriter’s imagination — and the vision of a filmmaker, whose art demands the creative interpretation of reality through the filter of a personal, subjective point of view, and whose craft requires innumerable technical decisions in the creative employment of the film medium and its production processes.”

“The cinema is an art form that requires conscious selective aesthetics judgments, but this fact shouldn’t erase the distinction between programs that depict avowedly fictional stories and those that address real-world topics without relying on the artifice of studio sets and actors’ performances. Documentary film thus enjoys a privileged status as a mediated representation of reality compared to fiction films. This distinction is not lost on viewers, who approach documentaries with a different frame of mind compared to fiction. Documentaries represent what Weik von Mosser (“Emotions,” 2014) calls “discourse of consequence,” meaning that viewers expect documentaries to potentially convey a message or have an impact on their actual lives, or at least on their understanding of the real world. This expectation is not diminished even though documentaries may evoke emotional responses in addition to presenting factual information.”

“The nature of a film’s reception depends to a great extent upon the expectations, knowledge, and values of its viewers. So a filmmaker frames her approaches to a topic based on the audience’s anticipated knowledge of and predisposition toward her topic.”

“The basic aesthetic elements of cinema may be summarised as visual composition, lighting, movement, color, direction of action, editing, sound (dialogue, sound effects, and music), and special effects. These elements of film craft may represent aspects of actual subjects in the real world, but they may also embody subjective perspective communicated by the filmmaker. For example, the angle of a shot may make a subject appear more powerful; a long take may convey a deeper sense of continuous reality than a series of quick cuts; and jux-tapositions of shots through editing may imply new associations and meanings through the comparison or contrast of images. Sound effects recorded in post production may add realism and emotional resonance to footage shot in the field without sync sound. Adding a musical soundtrack may lend an emotional tenor to a scene, reinforcing the message of the imagery. Even in direct cinema—the most pure mode of documentary style, which often relies on long takes and neutral camera angles—the filmmaker still makes decisions about where to put the camera, when to move it, and when to make the cut. There is no avoiding the conclusion that, as an art form, cinema molds its own reality as much as it presents that of the world.”

„Many documentaries engage in persuasive argument, desiring to convince the audience to adopt a particular point of view toward the subject matter. Toward this end, filmmakers employ age-old strategies of rhetorical argument to engage and persuade their audience. Following Aristotle, documentarians employ three primary rhetorical styles: (1) Logos—the use of factual evidence and reasoning—through logical argument, empirical visual representation (e.g. photographs or original footage), and statistical evidence (e.g., charts and graphs) to embody or clarify ideas; (2) Ethos—the reliance on authority, expertise, and ethical stature, established through testimony from recognized experts or those who speak from personal experience; and (3) Pathos—the appeal to values and emotions, often through cultivating an identification with sympathetic subjects, or feelings of anger toward their antagonist.“

„Documentary films certainly qualify as forms of communication or „speech“, but it is crucial to respect the difference by which a viewer receives an audio-visual presentation, in contrast to a written or spoken address. Speeches based on factual evidence or appeals to authority are primary left-brain, analytical activities. The listener weighs the evidence and reaches a conclusion, similar to the process in a jury trail. However, an image is „worth a thousand words“; it may appear to offer the strongest evidence of a state of affairs, as well as convey an emotional feeling, thus involving both analytical and intuitive mental faculties. For example, the juxtaposition of two images may establish an implicit link between them that creates a sort of „visual logic.“ The combination of an image and a musical theme may engage one‘s logical and emotional faculties simultaneously. The skilfulness of a persuasive documentarian often rests in his ability to weave these rhetorical threads together seamlessly.“

(The environmental documentary, Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, USA, 2017, John A. Duvall)