In this article we will discuss the different design elements that make an object can generate awkward interactions.

The 5 Psychological Concepts Creating Good Interaction

In the previous article, we talked about the principle of discoverability, for this principle is the result of 5 fundamental psychological concepts: affordance, signifiers, mappings, constraints, and feedback. It is these 5 concepts that will allow us to create when discovering an object, an experience coupled with optimal use of the object. Let’s now discover what these 5 concepts are and their implications in clumsy interactions.

Affordance :

We live in a world full of all kinds of objects, we use and discover new ones every day. Whatever the object we manage to master, and affordance is one of the first things that allow us to explain this. First named by the psychologist James J. Gibson, it refers to the relationship between a physical object and a person, a relationship that will help that person determine how to use an object. It describes all the actions made physically possible by an object. We can take the example of a closet, we know we can pull its doors open or push them shut. Don Norman brings a specification to the term affordance, he talks about perceived affordance, this point is very important because it is he who can show us how an affordance error can generate a clumsy interaction. This new term designates the actions that the user perceives as possible, as opposed to those that are actually possible. I was looking for a common example of a situation generated by an affordance problem, so I remembered buying a pair of pants some time ago. The pants had pockets on them, or at least that’s what I thought until I wore them and realized that they were fake pockets. This is an example showing that the action that I wanted to perform, that is to say to put my hand in my pocket, could not be done because the object did not allow it. But it is just as valid in the other direction sometimes actions cannot be performed because the user does not perceive them as possible. And this is where the concept of signifier comes into play.

The Signifiers :

If the affordances allow us to determine the possible actions, the signifiers tell us where we will be able to carry out this action. If one takes again the example of the pants it is the false pockets that were significant for me and led me to think that the action to put my hand in my pocket was possible at this precise place. These two concepts can be difficult to differentiate today in a world of new technology. For example, in the presence of a screen, we may tend to think that touching an icon is an affordance but this idea is false because the affordance corresponds to the action of touching the screen (wherever it is), the icon will represent the place where the action must take place, it is the signifier. Nowadays, for aesthetic reasons, it can be complicated to identify the signifiers, and therefore interacting becomes difficult. This is what we can observe with handleless closets; where should we take our opening action? Similarly, how do we choose which action to take, should we pull or push?

The handle answers all the questions, in addition to indicating where the action should be carried out, because of its location it shows us where the action is going to act, this is where the concept of mapping comes in.

The Mappings :

Mapping indicates the relationship between the two elements. For example, if we use baking trays with knobs, the mapping allows us to understand which knob is connected to which baking tray. The mapping is essential for the layout of the controls and displays. When the signifiers give a clear view of where to touch, the mapping allows us to instinctively understand what each control corresponds to. We will keep the example of the plates and see two interactions, one will be clumsy and the other not.

Here is a first hob composed of four plates. The buttons to operate each plate are placed next to each other. It is quite easy to realize that the two buttons on the left correspond to the left plates and the two buttons on the right to the right plates. However, to know which button corresponds to the top or bottom plate is more complicated, it is not possible to guess it naturally and therefore it must be tested with the risk of burning yourself.

Here is a second hob, more modern and based on tactile contact. The buttons to activate the plates are positioned like the plates, when we want to activate a plate we don’t ask ourselves and we are sure that it is the right one with this model.

It is important to specify that today, the majority of cooking tables with physical buttons have pictograms that make their understanding easier. Nevertheless, having this kind of hob I can attest to the fact that even with regular use I almost always check the pictogram to identify the right hob, so it’s simple but not intuitive. Let’s remember that the intuitive aspect of an object depends on the ability of the designer to provide the essential elements to understand the object and its limits.

These limits can be constraints.

The Constraints :

The constraint in itself does not need to be explained, it is known to everyone. On the other hand, we can explain the different types of constraints that are applied to objects by creators in order to limit the possible actions. There are four of them: physical, cultural, semantic, and logical.

The physical constraint is simple to understand, it is the one that limits the possible operations. For example, it is easy to realize that the wrong key is used to open the door because it will not make the lock work.

Cultural constraint is more difficult to grasp. Indeed, each culture defines a set of authorized actions in social situations. So if we misunderstand a culture, it is easy to make mistakes and create things that can be considered inappropriate. What’s more, these constraints are likely to change over time.

The semantic constraint is based on meaning, it is based on the knowledge of a situation in order to codify possible actions. For example, a windshield is there to protect the face of a person in a car, so it makes sense to put it in front of her. However, like cultural constraints, semantic constraints are also likely to evolve.

Finally, there is the logical constraint, based as its name suggests on logic. This constraint is particularly related to the principle of mapping. If we take again the example of the hob, it is logical to think that the knob on the top right will correspond to the plate on the top right and if this is not the case it is because there is a problem in the conception.

The Feedback

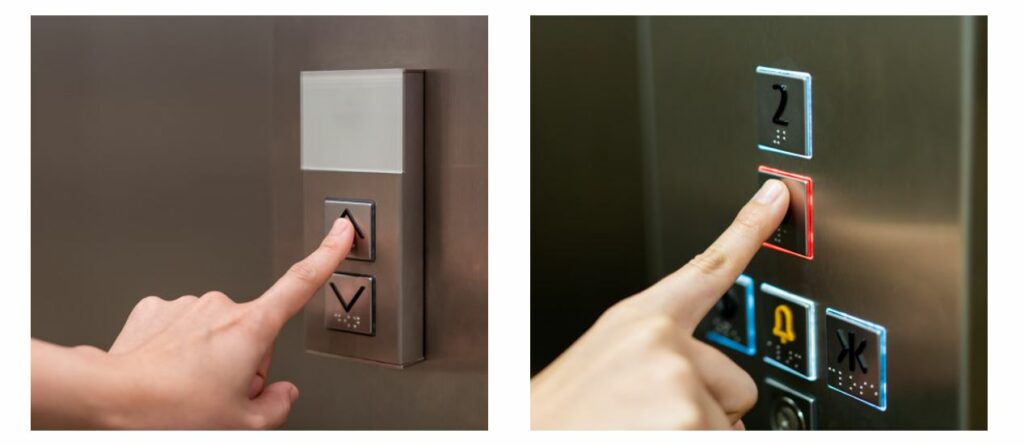

Finally, our last concept is feedback. When an object is designed so that we can identify affordance using the signifier, the mapping is clear and the constraints identified, the feedback will ensure that we have an understanding of the other four concepts. Feedback is the element that allows us to understand that our action has been taken into account. For example, when I use my oven and start my program, I hear a sound signal or see the oven light come on. Without this feedback, I am likely, in doubt, to repeat the action or even modify it, which can lead to awkward interactions. An obvious example is that of the elevator, if there is no visual or audible indication that the call has been answered we are likely to press the button again and again until the elevator arrives. Attention, this feedback must be thought to correspond to the action. Thus, if when we call the elevator an alarm sound is triggered we will certainly not stay waiting for it.

The Conceptual Model

The conceptual model allows explaining the functioning of an object in a simple way. It is the one that will allow us to create a simple mental model and make it easier to use: for example, when we see the “folder” or “file” icon on a computer. The simplest conceptual models are those that should be used for everyday objects because they remain in our memory and become our mental models. Beware, however, analyzing a conceptual model will create different mental models for different people, so let’s remember the engineer from the previous article who just forgot that his mental model is different from the users’ one. Conceptual models derive from the devices themselves and are created by the experience. Since an experience differs from one individual to another and unforeseen things can happen, the mental models it generates often end up being erroneous.s This is where the awkward interaction happens, if I have an erroneous conceptual model of an object, so will my use of it. A good conceptual model is used to understand how the elements will behave together and why they should be operated in a particular way. Let’s take the remote control, no matter what its shape or model I don’t know anyone who has used all the buttons on that object, let alone someone who can explain to me what each button corresponds to. In my opinion, the majority of people using remote control have a faulty conceptual model of it. Indeed, for it to be right, the person would have to understand all the actions that can be performed which is complicated when you don’t need to use them.

Conclusion

We have seen that many elements can influence our experience and our interactions with an object, negatively or positively. The concepts we have just mentioned are major points of vigilance when designing an object, to limit clumsy interactions.

Definition, in progress

- A clumsy interaction doesn’t happen at the moment we use the object, it was there before and can come from the designer and his personal vision of the use of the object.

- A Clumsy interaction can depend on the conception of an object and more specifically on the design of the experience related to this object when trying to manipulate it, activate it, make it work, and understand it.

Sources :

Book: The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman, 2020

Article: Affordance in user interface design, UX Collective, 2017