In our daily lives, we have access to countless objects, all of which can be replaced whenever we feel like it. Yet it seems harder to part with some of them. Who has never been reluctant to throw away a pair of shoes that have been worn for a long time even though they are damaged and worn out, and this without any logical reason? I propose to explore our connection to the object and how our emotions towards these objects impact our interactions with them and can make them awkward.

The place of emotions in our lives

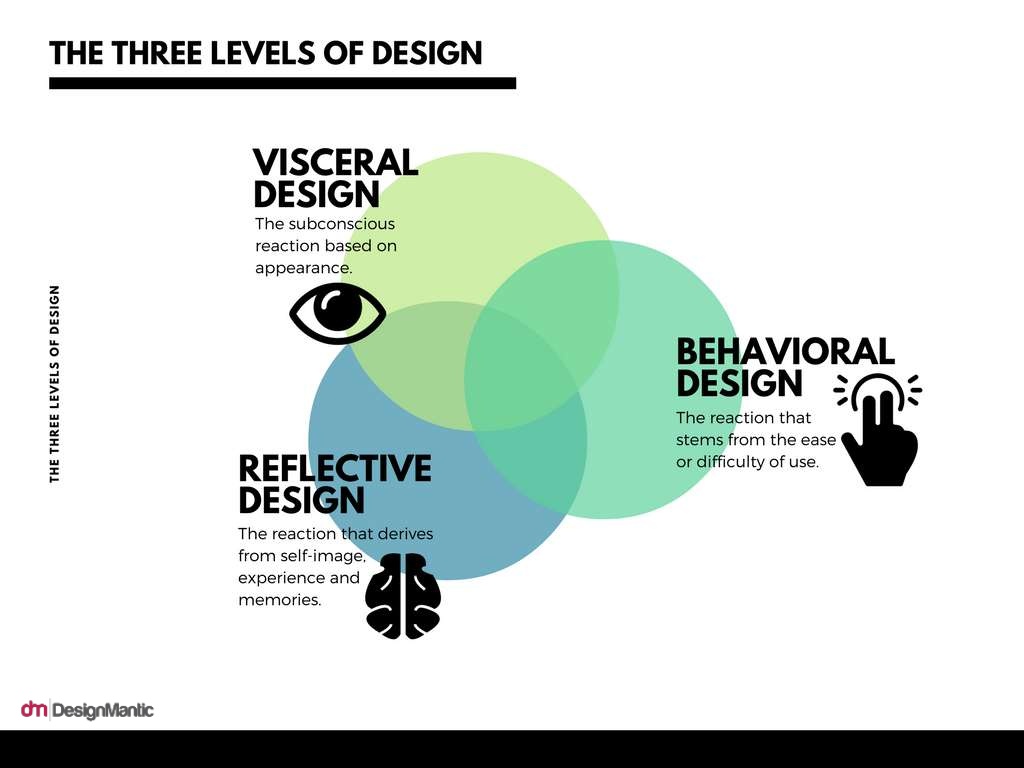

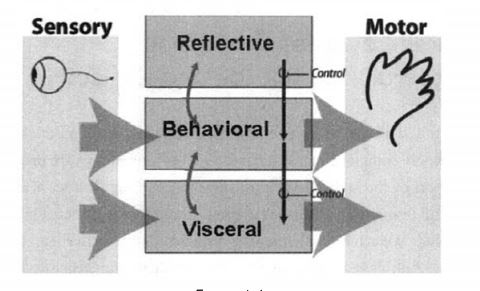

Emotion is the manifestation of a feeling that provokes a disorder. Emotions are considered to be animal, complex, and irrational and tend to be contrasted with so-called human, logical and rational cognition, yet it is emotions that allow us to make decisions even if unconsciously. In order to better understand, we need to look at human behavior, which is largely subconscious. In general, when information reaches the conscious mind, many judgments have already been made unconsciously. It is the affective system that prevails and makes a judgment, it is the affective system that will allow us to determine whether an environment or a situation is safe or dangerous, for example. The cognitive system will interpret external information and give it meaning, while the affect which is the system of a judgment of the outside world can be conscious or subconscious. When we feel an emotion, we make a conscious experience of the affect and this allows us to attribute a cause to it as well as to identify its object. Let’s take the example of a 3 meter long, fairly wide board that we have to cross. If it is on the ground or placed at a low height we will do it without apprehension. Now if we take the same board and place it 50 meters above the void our reaction will be completely different. The reflected part of our brain will not see any difference but the emotional system, at the visceral level, will generate a feeling of intense fear. This example shows us that the affective system functions independently of conscious thought. This same system also allows us to make decisions. Contrary to what we think, it is not rational thoughts that allow us to make decisions, even simple ones, but our emotions. Cognition interprets and understands the world around us while emotions allow us to make quick decisions about them. In fact, if we go to a bakery to choose a cake, it is not logic that will allow us to choose, but affect that will tell us which cake will generate more taste pleasure. However, there is another parameter to take into account. Studies of emotions have shown that they originate at three different levels of the brain: visceral, behavioral, and reflective. The first one is automatic and defines what is good or bad, it is the beginning of the affect process. The behavioral level focuses on what comes out of the visceral level and improves or inhibits a behavior that will be triggered. The reflective level streamlines environmental information to influence the behavioral level. In our everyday life this is how these 3 different levels can appear:

- When we go to a haunted house we experience visceral reactions of surprise and fear,

- When we cut meat with a knife, we experience the behavioral level by performing repetitive gestures with minimal concentration so that we can cut ourselves at certain times.

- When we play a complex music score it is the reflective level that comes into play; we analyze the score to play it and our fingers play instinctively.

It is essential to understand that the first two levels are subconscious, which is what allows us to do several things at the same time such as driving and thinking about something at the same time. These levels are therefore of paramount importance in the way we interact because emotions influence our behavior.

Last interesting point, these 3 levels can find themselves in opposition and take precedence over others depending on the situation and the person, that’s why we do not all react in the same way. A simple example, a year ago I made a skydiving jump with a friend, we thought about it at the same time and decided to go for it on a whim. We scheduled the jump two days before and from then on our reactions and emotions were different. At first, my friend was a little apprehensive about the jump, while I felt nothing but excitement and anticipation. On the day of the jump, she had no apprehension at all and wanted to jump, while I was scared when I got on the plane and started shaking and clenching my teeth and couldn’t control myself. Finally, we both jumped, a lot of emotions came up and the adrenaline and excitement on landing were immense. You can see here that the different levels did not arrive in the same order for my friend and me. She first felt fear, the visceral part at first, then the reflective part intervened and the behavior that resulted when the time came was only due to the excitement. For me, the reflection came at the beginning, when I programmed the jump but in the plane, the visceral part generated fear.

We have just seen how emotions are created, how they are ours, and how they influence our behaviors and reactions, so it is time to think about how they relate to objects.

The generation of an emotion in relation to an object

Emotions change our behavior in a time that can be very short in order to give an immediate response to a situation that makes us feel positive or negative. When we are in a negative, stressed, anxious state, our brain focuses on one thing, the source of this state, and the emotional system is alerted at all levels so that there is a very quick reaction in case of a problem. Conversely, when we are in a positive state, we are open to what surrounds us, much more curious and creative. What does this have to do with design? This is it. A relaxed, joyful designer in a good mood is more creative.

We can also ask ourselves how through their design objects generate positive or negative emotions? To do this, let’s go back to our 3 levels and link them to design, so that gives: visceral design, behavioral design, and reflective design.

What is the impact of emotions in the generation of awkward interactions? It has been proven through different studies such as Masaaki Kurosu and Kaoru Kashimura, researchers that the attractiveness of an object influences its usability.

Visceral design is what gives us a good or bad first impression and symbolizes the attractiveness of an object, which is personal to us and felt as soon as we see the object. At this level, the information about the object is already pre-made and preconceived based on its appearance, its touch, it’s feeling.

Some time ago I bought a very simple object, a pen. It has no particular function, has only one color of ink, and is not refillable. So why did I buy it? This pen is a unicorn pen with fun colors that made me laugh, that’s all. When I bought it I didn’t think about the fact that it could be more complicated to use because of its shape and weight, nor did I think that its shape would make it impossible to fit in a pencil case and yet I don’t regret this purchase or complain about its use. The awkward interactions that I encounter with this object come from the characteristics of its appearance or as it is these same characteristics that pushed me to buy it I don’t think about it and I adapt myself.

Behavioral design is the experience we have of the object through its use. This experience is based on several things: function, performance, and usability. At this point, the positive or negative effects depend on the emotion generated by the use, was it frustrating or amusing?

I’ve had various TV remote controls, one of them leaves me with a special memory. When I first had it in my hands I tried to turn it on by pressing the on/off button, until then everything was understandable, but nothing happened. I tried, again and again, to check the presence of batteries, the position of the batteries and try again. It took me a good 5 minutes of unsuccessful testing to understand that for the remote control to work I had to stay pressing the button for 5 to 10s. This experience was quite frustrating and after this one every time I used this remote control I found the ignition time incredibly long. Here the emotions generated by this awkward interaction made it unpleasant and unsatisfying for all the interactions with this remote that followed.

Reflective design is about the message, culture, and meaning of the product and its use. It is completely conscious and it is about the interpretation, understanding, and resonance of the object. The reflective level determines a person’s overall impression of an object. An object is more than its functionality, its value is how it meets people’s emotional needs, how it allows them to give them the image they want. Let’s imagine that I have a passion for cars and more precisely for speed, I have the opportunity to buy a very fast Ferrari car, I buy it for myself knowing that no matter which car I own the speed limit will always be the same. So I have a race car that I will never go very fast with.

Conclusion

The emotion and the attractiveness of the object have an influence on us, however we must keep in mind that this notion of attractiveness can be different from one culture to another. Does this cultural difference have an impact on interactions?

Definition, in progress

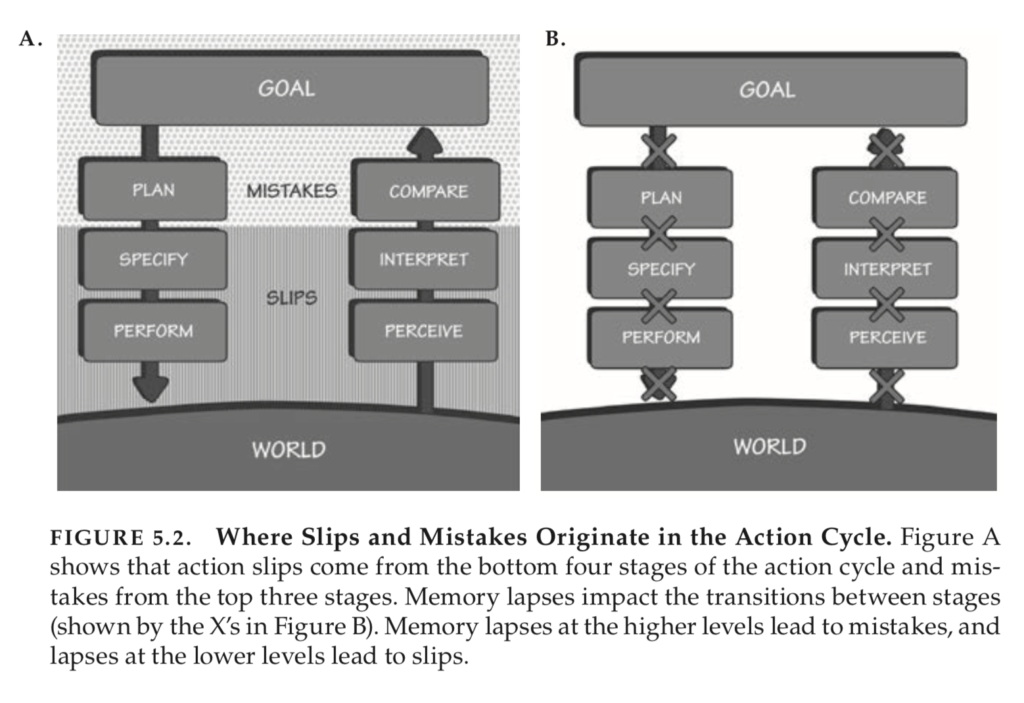

- A Clumsy interaction doesn’t happen at the moment we use the object, it was there before and can come from the designer and his personal vision of the use of the object.

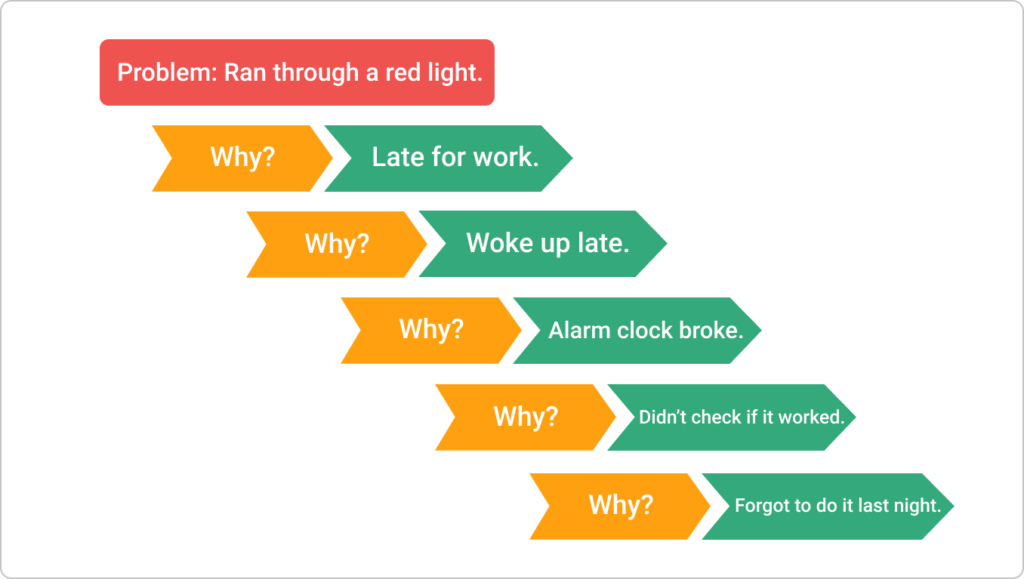

- A Clumsy interaction can depend on the conception of an object and more specifically on the design of the experience related to this object when trying to manipulate it, activate it, make it work, and understand it.

- A Clumsy interaction has several causes, one of which is mostly conceptual. When the origin of the awkward interaction is inappropriate and deliberate behavior, it is then a human error of the user.

- A Clumsy interaction can be the result of a lack of curiosity.

- A Clumsy interaction depends on the level and type of emotions the object will generate in the user before, during, or after its use.

Sources:

Book: Emotional Design, Don Norman, 2003

Article: Les émotions dans le design – les trois niveaux du design, UX-FR