Do you catch yourself recognising whose track/song you are listening to when you’re just shuffling randomly through Spotify, even before you look at the artist name? This is because successful music producers have a way to make sure you can instantly recognise them. This is quite beneficial, because it imprints into the listener’s mind and makes them more likely to recognise and share the artist’s future releases with their network.

So how do musicians/music producers do this? There are some key points that can easily help you understand this occurence better.

1) There’s no shortcut!

You know the 10.000 hour rule? Or as some have put it in the musical context- 1,000 songs? There’s really no way around it! This aplies to any skill in life, not just music. However, usually the end consumer never really knows how many songs an artist actually never releases. Those are all practice songs. For every release that you see out there there might be 100s of other unreleased songs done prior to it. if the musician just keeps creating instead of getting hung up on one song, they will eventually grow into their own unique way of structuring, as well as editing songs.

2) They use unique elements

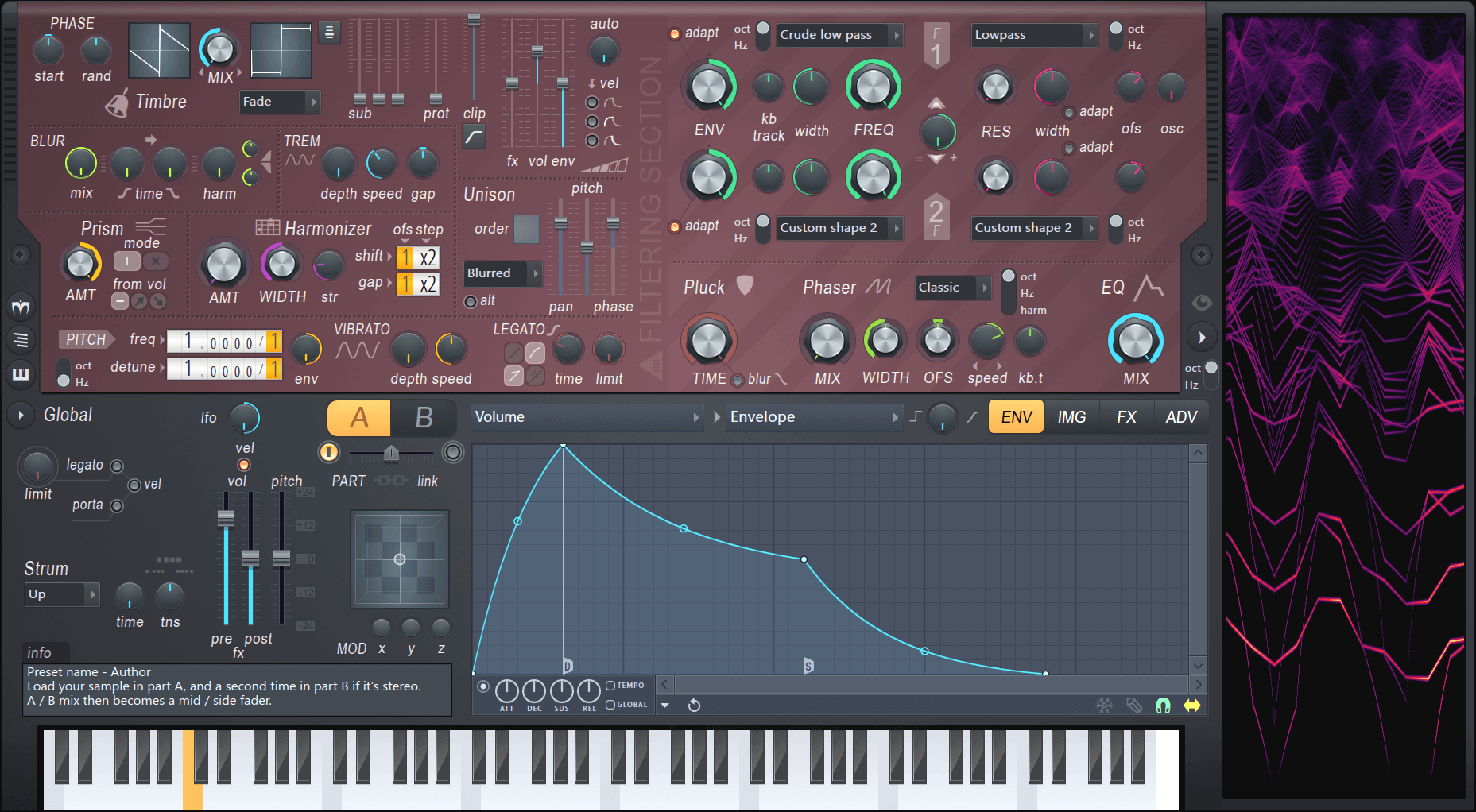

So many producers/musicians use samples from Splice, which leads to the listener feeling like they’ve already heard a song even if they haven’t. Songs get lost in the sea of similar musical works, but every now and then, something with a unique flavour pops up and it’s hard to forget. Musicians who make their own synth sounds, play exotic instruments or even their own dit instruments are the ones that stick around in our minds.

3) Using the same sound in multiple songs

This is the easiest and most obvious way in which musicians/producers show their own style. You might hear a similar bass, or drum pattern in mutiple songs/tracks from the same musician. In rap/hiphop, you will also hear producer tags (e.g. “Dj Khaled” being said in the beginning of each track).

4) Great Musicians/Producers don’t stick to one style/trend

Music has existed for so long and progressed so fast lately, that it is hard to stand out, especially if you stick to genres strictly. Nowadays, great musicians will come up with their own subgenres or mix in few different ones into a musical piece. You won’t ever really remember the musicians or the producers who are just following in the footsteps of the greats who have already established a certain genre. If you can’t quite put your finger on why you like someone’s music so much and why they sound “different”, they are probably experimenting with a combination of different genres.