Filmkameras waren für die längste Zeit das bevorzugte Werkzeug der Blockbuster-Industrie. Der hervorragende Dynamikumfang sowie das scharfe Bild waren filmische Eigenschaften, die man nicht aufgeben wollte. Zudem waren Filmkameras perfekt gebaut für den Einsatz auf großen Sets mit langen Drehtagen. Das änderte sich, als ARRI die Filmlandschaft auf den Kopf stellte und 2009 mit der ARRI Alexa einen Durchbruch im Digitalbereich gelang. Roger Deakins (Kameramann von Filmen wie “Die Verurteilten”, “Blade Runner 2049” oder “James Bond 007: Skyfall”) sagte später in einem Interview: “This Camera has brought us to a point where digital is simply better.”

Dass sich seither die Filmlandschaft stark gewandelt hat, steht außer Frage. Filme, die auf Celluloid-Film gedreht werden gestalten heutzutage die Ausnahme. Filmrollen sind teuer und kosten viel Geld in der Entwicklung und Lagerung, zudem ist eine Filmkamera wesentlich schwerer bedienbar. Damit am Ende ein scharfes und korrekt belichtetes Bild entsteht, verlangt es ebenfalls nach einem guten Fokuszieher sowie jemand Erfahrenem hinter der Kamera. Digitaler Film ist hingegen wesentlich einfacher in der Bedienung, denn was man sieht ist in der Regel auch das, was man filmt. Vor allem kleinere Produktionen profitieren immens von dieser Entwicklung und den geringeren Kosten, ohne dabei wirklich an Qualität einbüßen zu müssen. Wenn man nun die Vorteile mit den Nachteilen vergleicht liegt die Antwort auf der Hand – Digitalbild ist dem Analogfilm überlegen, oder?

Drehbuchautor und Regisseur Quentin Tarantino sagte in einem Interview folgendes: “I have always believed in the magic of movies and to me the magic of movies is connected to 35mm.” Obwohl die Bildqualität von Digitalkameras mittlerweile nahezu perfekt ist, von gestochen scharfer Auflösung bis hin zur akkuraten Farbwiedergabe, sind es gerade die Makel des analogen Films, die Enthusiasten als “Magie” betiteln. Zu diesen Charakteristiken gehören die Körnung, rote Lichthöfe, kleine Verschiebungen von Bild zu Bild und natürlich auch die Farben des jeweiligen Filmstocks sowie Charakteristiken die in der je nach Art der Entwicklung des Films entstehen. Schließlich beeinflusst auch die Wiedergabe des finalen Films auf einem Laufbildprojektor (statt dem digitalen Pendant) die Erfahrung des Zuschauers. Viele dieser Faktoren spielen eine große Rolle für den Look des finalen Bilds und können bei der kleinsten Abweichung bereits einen wahrnehmbaren Einfluss auf das Werk ausüben. “It certainly got a lot of advantages that film never had, consistency being a really big one”, sagte Roger Deakins über digitale Kameras und Projektoren. Wenn von der Magie des Analogfilms gesprochen wird, wird oftmals auf jene Abweichungen und Ungenauigkeiten verwiesen. Die Tatsache nicht genau zu wissen, was sich am Ende des Tages in dieser schwarzen Box versteckt, lässt viele Liebhaber romantisierend über Film sprechen.

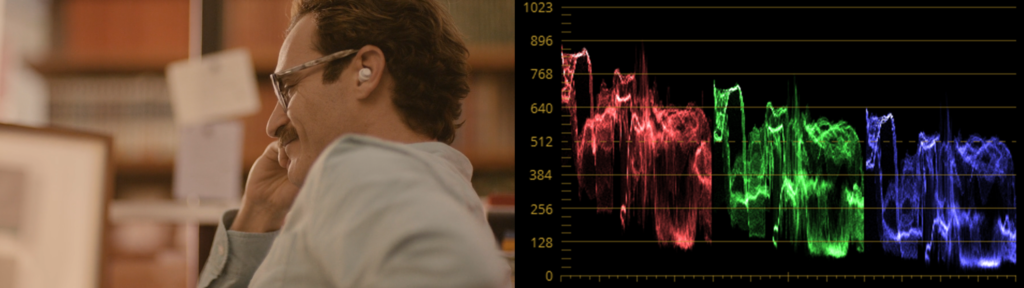

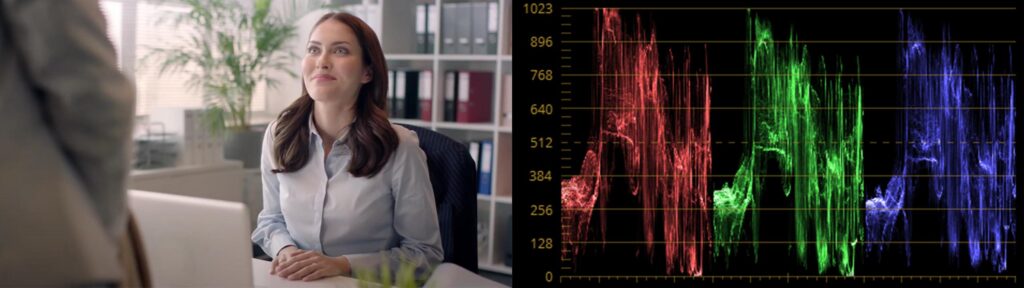

Steve Yedlin, Kameramann von Filmen wie “Knives Out” oder “Star Wars: The last Jedi” vertritt einen klaren Standpunkt: “As artists, to put all of our faith in the illusory simplicity of bundled systems instead of understanding the analytic components that are the undeniable building blocks of the process is to give up our control and authorship.” Dabei redet Yedlin nicht nur von Filmkameras, sondern auch von digitalen Kameras. Ihm zufolge sei die in der Filmbranche dominante Narrative, nämlich dass die Wahl einer bestimmten Kamera oder Filmstock maßgeblich für den finalen Look und somit auch für die Wahrnehmung und Erfahrung des Zuschauers zuständig sei, schlichtweg falsch. Yedlin plädiert eine Kamera nicht als ein Stilmittel zu sehen, sondern als ein System zu betrachten, das rohe Informationen über das Licht, das durch die Optik eindringt, speichert. Die Ästhetik entsteht laut Yedlin erst später in der Nachbearbeitung, wenn mit den Daten gearbeitet wird und nicht mit dem Gerät, das die Daten aufzeichnet. Als Beweis dafür führt er in seiner “Display Prep Demo” einen Vergleich zwischen 35mm Film und digitalen Bildmaterial auf. Beide sehen zum verwechseln ähnlich aus und unterstützen seine These, trotzdem verweist Yedlin darauf, dass man noch mehr testen, evaluieren und programmieren müsste, um perfekte Ergebnisse in der Gestaltung eines korrekten Filmlooks erzielen zu können.

Ob man die Ästhetik des Celluloid Films nun mag oder nicht, sei dahingestellt, was Yedlin beschreibt ist ein grundlegendes Missverständnis in der Debatte. Dass Hersteller ihre Produkte verkaufen wollen und mit halb wahren oder irreführenden Aussagen locken, gießt hierbei leider nur Öl ins Feuer. Fakt ist jedoch, dass moderne digitale Filmkameras mit ihrer Qualität an einem Punkt angekommen sind, an dem man mit einer Daten schonenden Postproduktion-Pipeline vollste kreative Freiheit genießt, und Freiheit ist zumindest in meinen Augen das wichtigste Gut eines jeden Künstlers.

Filmkameras waren für die längste Zeit das bevorzugte Werkzeug der Blockbuster-Industrie. Der hervorragende Dynamikumfang sowie das scharfe Bild waren filmische Eigenschaften, die man nicht aufgeben wollte. Zudem waren Filmkameras perfekt gebaut für den Einsatz auf großen Sets mit langen Drehtagen. Das änderte sich, als ARRI die Filmlandschaft auf den Kopf stellte und 2009 mit der ARRI Alexa einen Durchbruch im Digitalbereich gelang. Roger Deakins (Kameramann von Filmen wie “Die Verurteilten”, “Blade Runner 2049” oder “James Bond 007: Skyfall”) sagte später in einem Interview: “This Camera has brought us to a point where digital is simply better.”

Dass sich seither die Filmlandschaft stark gewandelt hat, steht außer Frage. Filme, die auf Celluloid-Film gedreht werden gestalten heutzutage die Ausnahme. Filmrollen sind teuer und kosten viel Geld in der Entwicklung und Lagerung, zudem ist eine Filmkamera wesentlich schwerer bedienbar. Damit am Ende ein scharfes und korrekt belichtetes Bild entsteht, verlangt es ebenfalls nach einem guten Fokuszieher sowie jemand Erfahrenem hinter der Kamera. Digitaler Film ist hingegen wesentlich einfacher in der Bedienung, denn was man sieht ist in der Regel auch das, was man filmt. Vor allem kleinere Produktionen profitieren immens von dieser Entwicklung und den geringeren Kosten, ohne dabei wirklich an Qualität einbüßen zu müssen. Wenn man nun die Vorteile mit den Nachteilen vergleicht liegt die Antwort auf der Hand – Digitalbild ist dem Analogfilm überlegen, oder?

Drehbuchautor und Regisseur Quentin Tarantino sagte in einem Interview folgendes: “I have always believed in the magic of movies and to me the magic of movies is connected to 35mm.” Obwohl die Bildqualität von Digitalkameras mittlerweile nahezu perfekt ist, von gestochen scharfer Auflösung bis hin zur akkuraten Farbwiedergabe, sind es gerade die Makel des analogen Films, die Enthusiasten als “Magie” betiteln. Zu diesen Charakteristiken gehören die Körnung, rote Lichthöfe, kleine Verschiebungen von Bild zu Bild und natürlich auch die Farben des jeweiligen Filmstocks sowie Charakteristiken die in der je nach Art der Entwicklung des Films entstehen. Schließlich beeinflusst auch die Wiedergabe des finalen Films auf einem Laufbildprojektor (statt dem digitalen Pendant) die Erfahrung des Zuschauers. Viele dieser Faktoren spielen eine große Rolle für den Look des finalen Bilds und können bei der kleinsten Abweichung bereits einen wahrnehmbaren Einfluss auf das Werk ausüben. “It certainly got a lot of advantages that film never had, consistency being a really big one”, sagte Roger Deakins über digitale Kameras und Projektoren. Wenn von der Magie des Analogfilms gesprochen wird, wird oftmals auf jene Abweichungen und Ungenauigkeiten verwiesen. Die Tatsache nicht genau zu wissen, was sich am Ende des Tages in dieser schwarzen Box versteckt, lässt viele Liebhaber romantisierend über Film sprechen.

Steve Yedlin, Kameramann von Filmen wie “Knives Out” oder “Star Wars: The last Jedi” vertritt einen klaren Standpunkt: “As artists, to put all of our faith in the illusory simplicity of bundled systems instead of understanding the analytic components that are the undeniable building blocks of the process is to give up our control and authorship.” Dabei redet Yedlin nicht nur von Filmkameras, sondern auch von digitalen Kameras. Ihm zufolge sei die in der Filmbranche dominante Narrative, nämlich dass die Wahl einer bestimmten Kamera oder Filmstock maßgeblich für den finalen Look und somit auch für die Wahrnehmung und Erfahrung des Zuschauers zuständig sei, schlichtweg falsch. Yedlin plädiert eine Kamera nicht als ein Stilmittel zu sehen, sondern als ein System zu betrachten, das rohe Informationen über das Licht, das durch die Optik eindringt, speichert. Die Ästhetik entsteht laut Yedlin erst später in der Nachbearbeitung, wenn mit den Daten gearbeitet wird und nicht mit dem Gerät, das die Daten aufzeichnet. Als Beweis dafür führt er in seiner “Display Prep Demo” einen Vergleich zwischen 35mm Film und digitalen Bildmaterial auf. Beide sehen zum verwechseln ähnlich aus und unterstützen seine These, trotzdem verweist Yedlin darauf, dass man noch mehr testen, evaluieren und programmieren müsste, um perfekte Ergebnisse in der Gestaltung eines korrekten Filmlooks erzielen zu können.

Ob man die Ästhetik des Celluloid Films nun mag oder nicht, sei dahingestellt, was Yedlin beschreibt ist ein grundlegendes Missverständnis in der Debatte. Dass Hersteller ihre Produkte verkaufen wollen und mit halb wahren oder irreführenden Aussagen locken, gießt hierbei leider nur Öl ins Feuer. Fakt ist jedoch, dass moderne digitale Filmkameras mit ihrer Qualität an einem Punkt angekommen sind, an dem man mit einer Daten schonenden Postproduktion-Pipeline vollste kreative Freiheit genießt, und Freiheit ist zumindest in meinen Augen das wichtigste Gut eines jeden Künstlers.

Links:

https://www.arri.com/en/company/about-arri/history/history

https://youtu.be/BON9Ksn1PqI

https://youtu.be/p2Z4UvAdE7E

https://www.yedlin.net/DisplayPrepDemo/index.html