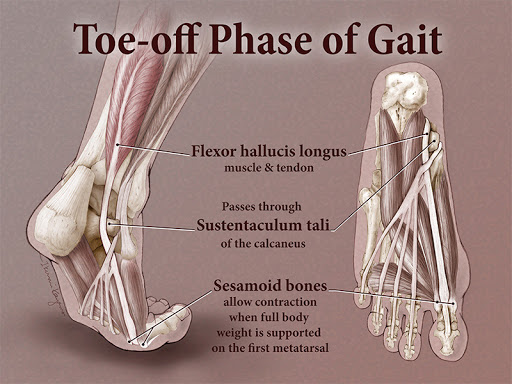

The main goal of scientific illustration is to translate scientific information into a visual representation that helps the reader or viewer to better understand the topic. Creating a scientific illustration involves multiple steps that may vary depending on the project.

At first the most important thing is to research the hell out of your subject! It may take some time, but it is extremely important to accurately share the information. When working with a scientist there will be provided information, but you still have to sit down and wrap your brain around it. Don’t forget to look at existing or similar work on the subject. It’s good to know what’s out there.

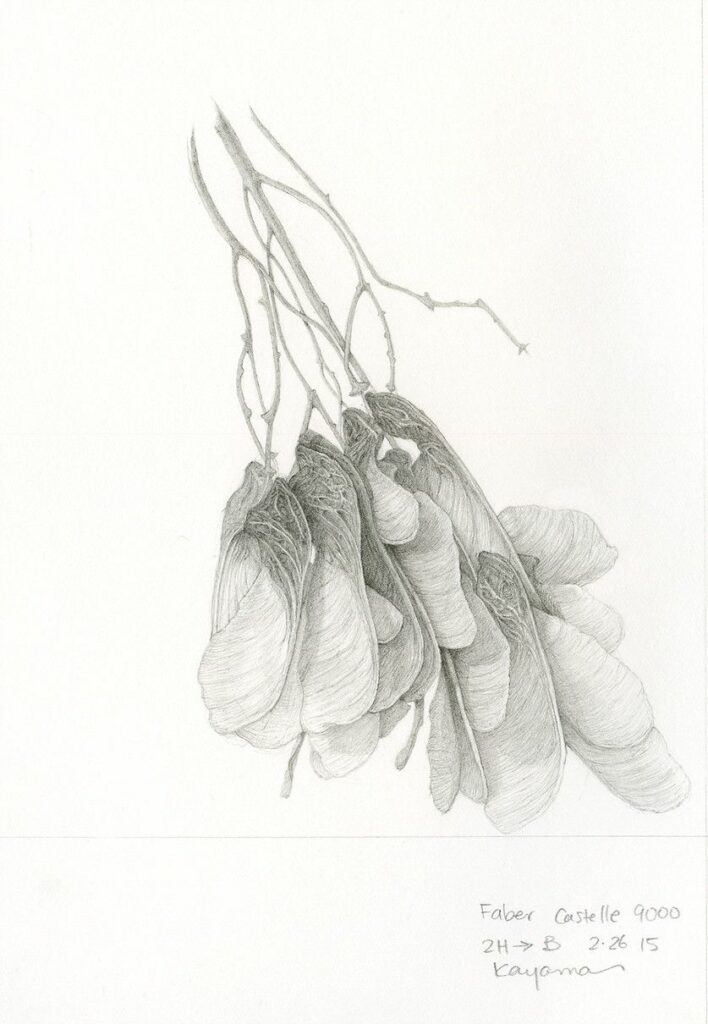

The next thing on your to-do list is to create preliminary sketches. Visualize what you have in mind and make as many sketches as you feel like. The more you sketch the more you can edit, revisit and adapt later on. You can also sketch the layout of the finished product (e.g. an informative poster) to get a feel for the needed space and dynamic of different parts.

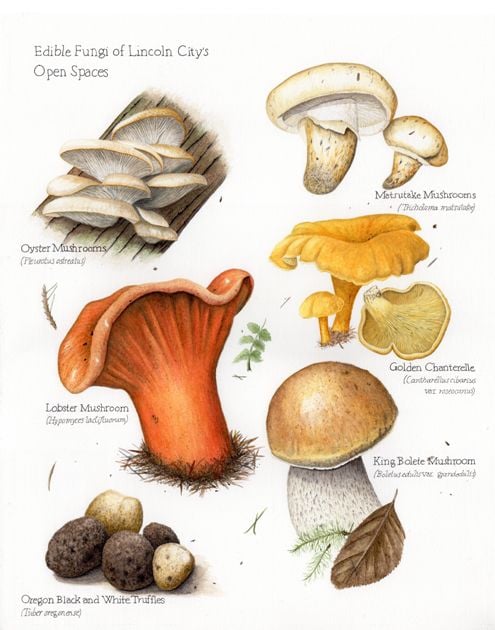

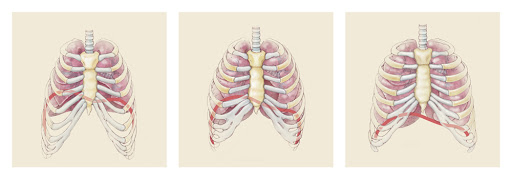

After doing your sketching you can try out different illustration techniques. Will it be digital or analog? What color palettes will you use? By practicing and using different types of media and get a feel for which style fits your project best and find out how to get the best result.

Now that you made your sketches and tried different methods it is time to decide on the overall composition and transfer your drawing to editing software. Afterwards it’s time to start working on your final illustration. Once you get a first draft you can talk to the scientist that you cooperate with and discuss your illustration. Make it an iterative process and revise your illustration if needed. Once you and your collaborator are on the same page you can finalize the project.

I got this information from an article by Kara Perilli about making a scientific illustration on the Current, a blog from The Franklin Institute. She writes about the process in more detail and via example from her own project.

https://www.fi.edu/blog/making-a-scientific-illustration

I also found this video about Nora Sherwood on her journey and career as a scientific illustrator. She is talking about her creative process, her desire to make people think about the world and nature as well as her wish to invoke curiosity and pass on knowledge.