Joy and Beauty

Joy and beauty are two terms which are close to each other when it comes to our perception. Looking at art that we perceive as beautiful, watching an aesthetically pleasing movie, strolling through a beautiful landscape—all those activities evoke the feeling of (en)joy(ment).

According to Denis Dutton the most powerful theory of beauty—closely linked to joy—we yet have comes surprisingly from an expert on barnacles and worms and pigeon breeding: Charles Darwin. Many would say joy/beauty is whatever moves you personally or it is in the (culturally conditioned) eye of the beholder. There are many differences among cultures, but there are also universal, cross-cultural aesthetic pleasures and values. [1]

“We need to reverse-engineer our present artistic tastes and preferences and explain how they came to be engraved in our minds by the actions of both our prehistoric, largely pleistocene environments, where we became fully human, but also by the social situations in which we evolved.” —Denis Dutton

What do we experience as joyful/beautiful?

Answering this question is complex, because the things we experience as joyful/beautiful are so different and foremost they are omnipresent—in nature, in arts, in literature, etc. However, Denis Dutton attempts to reconstruct a Darwinian evolutionary history of our artistic and aesthetic tastes. Dutton has no doubt that the experience of beauty, with its emotional intensity and pleasure, belongs to our evolved human psychology. He explains beauty as an adaptive effect, which we extend and intensify in the creation and enjoyment of works of arts and entertainment. [2]

Two primary mechanisms of evolution:

- natural selection

Natural selection is random mutation and selective retention along with our basic anatomy and physiology—such as the evolution of the eye. It explains many basic revulsions—such as the minging smell of rotting meat, the fear of snakes. But it also explains pleasures—liking for sweets, fat and protein, etc. - sexual selection

Sexual selection operates very differently. The most popular example is the peacock’s tail—it did not evolve for survival, but rather results from the mating choices made by peahens.

According to this idea, we can say that the experience of beauty is one of the ways that evolution has of arousing interest of fascination in order to encourage us toward making the most adaptable decisions for survival and reproduction. As in the last blogpost mentioned an important source of aesthetic pleasure are landscapes—pastoral scenes. Regardless from culture people like this particular kind of landscapes. People do not only like it but experiences it as joyful/beautiful. Noticeable is that this particular kind of landscape happens to be similar to the Pleistocene savannas where we evolved. [3]

“The ideal savanna landscape is one of the clearest examples where human beings everywhere find beauty in similar visual experience.” —Denis Dutton

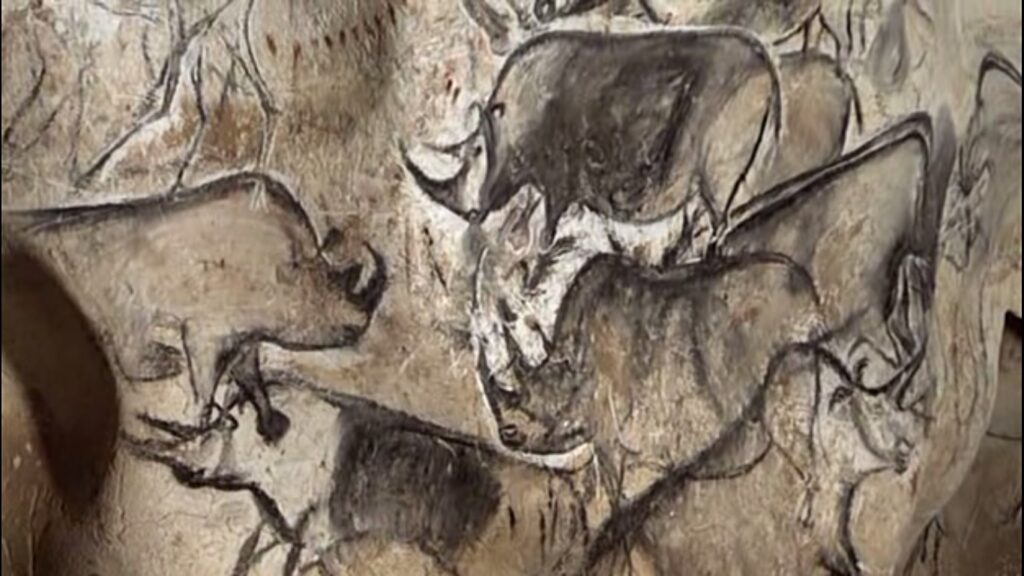

This universal experience of beauty in nature can also be recognized in an universal experience of beauty in art. According to Dutton it is widely assumed that the earliest human artworks were stupendously skillful cave paintings.

But artistic and decorative skills are actually much older than that. Realistic sculptures of women and animals, shell necklaces, as well as ochre body paint, have been found from around 100,000 years ago. And even older than this are the Acheulian hand axes. Or the oldest stone tools, which go back about two and a half million years—choppers of the Olduvai Gorge, East Africa. These tools were around for thousands of years until around 1.4 million years ago when Homo erectus started shaping Acheulian hand axes. Those were made out of thin stone blades, sometimes rounded ovals and very often in symmetrical pointed leaf or teardrop forms. Those axes were found across Asia, Europe and Africa. A sheer number of those axes were created, which indicates that they can not have been made for butchering—many of them also do not indicate any evidence of wear. Trough the use of symmetry, attractive materials and their meticulous workmanship those axes are perceived as beautiful—even nowadays.

According to Dutton these ancient artifacts could have been the earliest known works of art, practical tools transformed into captivating aesthetic objects—tools to function as „fitness signals“— displays that are performances like the peacock’s tail, except that, unlike hair and feathers, the hand axes are consciously cleverly crafted. Those competently made hand axes could have acted as an indicator for desirable personal qualities: intelligence, conscientiousness and in addition, access to rare materials (= wealth). Those skills were used to increase status—over tens to thousands of generations. Interesting about that is that we do not really know how this idea has been conveyed, since the Homo erectus did not have language. Stretching over a million years, the hand axe tradition is the longest artistic tradition in human and proto-human history. [4]

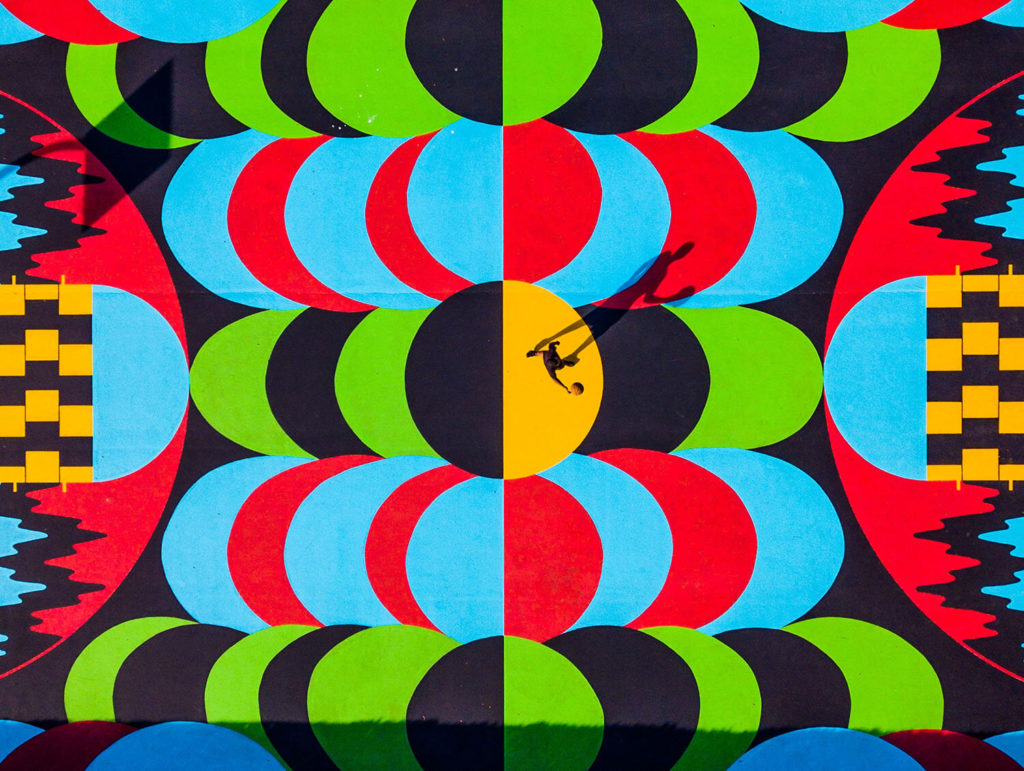

The Beauty in Skilled Performance

Nowadays, virtuosos technique is used to create imaginary worlds in fiction and in movies, to express intense emotions with music, painting and dance. But still, one fundamental trait of the ancestral personality persists in our aesthetic cravings: the beauty we find in skilled performances. From Lascaux to the Louvre: human beings have a permanent innate taste for virtuoso displays in the art—we find beauty in something done well. Therefore, what we experience as joyful/beautiful is not necessarily a product of our subjective perception or influenced by culture. Furthermore our perception of beauty and joy has been handed down from the skills and emotional lives of our ancient ancestors—it is deep in our minds. Our perception and reaction to images, expression of emotion in arts, music, etc. has been with us ever since. [5]

Sources

[1] TED. Denis Dutton: A Darwinian theory of beauty. URL: https://www.ted.com/talks/denis_dutton_a_darwinian_theory_of_beauty (last retrieved December 01, 2020)

[2] ebda.

[3] ebda.

[4] ebda.

[5] ebda.